When Bolshevik Schooling Came to America

The fourth in a series . . .

In my last essay in this series on the relationship between government and the education of children (“Why Government Schooling Came to America”), I provided a brief intellectual history of how and why a system of government schooling was established in the United State during the nineteenth century. The philosophic seeds of compulsion, collectivism, and statism in American schooling were first planted in the 1820’s and they came to fruition a few decades later.

As we saw, nineteenth-century American education “reformers” were deeply influenced by the Prussian model of government-run education. As I wrote:

The primary objectives of America’s new Prussianized education system were fivefold: first, to replace parents with the State as the primary influence on the education of children; second, to elevate and promote the interests of the State; third, to substitute America’s highly individualistic and laissez-faire social-political system with one that was collectivistic and statist in nature; fourth, to create a new kind of citizen, whose primary virtues would be self-sacrifice, compliance, obeisance, and conformity; and, fifth, to Americanize and Protestantize the teeming hordes of Irish-Catholics who were coming to the United States (and then the waves of immigrants coming to the U.S. after the Civil War from southern and eastern Europe).

In other words, America’s government school system was established by and for the State (i.e., whomever was in control of the government at any particular time and place).

Make no mistake about it: government schooling is backed by the coercive force of the State. Compulsory attendance laws must, for instance, be obeyed at the risk of legal punishment, which includes arrest, imprisonment, fines, and potentially the seizing (aka kidnapping) of one’s children. These are indisputable facts, and you are kidding yourself if you think otherwise.

The influential nineteenth-century English philosopher Herbert Spencer identified exactly what government schooling is and what it means in his Social Statics (1851):

For what is meant by saying that a government ought to educate the people? why should they be educated? what is the education for? Clearly to fit the people for social life—to make them good citizens. And who is to say what are good citizens? The government: there is no other judge. And who is to say how these good citizens may be made? The government: there is no other judge. Hence the proposition is convertible into this—a government ought to mould children into good citizens, using its own discretion in settling what a good citizen; is, and how the child may be moulded into one. It must first form for itself a definite conception of a pattern citizen; and having done this, must elaborate such system of discipline as seems best calculated to produce citizens after that pattern. This system of discipline it is bound to enforce to the uttermost. For if it does otherwise, it allows men to become different from what in its judgment they should become, and therefore fails in that duty it is charged to fulfil.[1]

A few years later, the other great English classical liberal, John Stuart Mill, spelled out in On Liberty (1859) the not-so-hidden means and ends of government schooling.

A general state education is a mere contrivance for moulding people to be exactly like one another; and the mould in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government, whether this be a monarch, a priesthood, an aristocracy, or the majority of the existing generation in proportion as it is efficient, it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body.[2]

America’s government schools are and always have been political institutions. They must always serve the ideological-political interests of some individual or group. But as I argued in the first two essays in this series (“How the Redneck Intellectual Discovered Educational Freedom—and How You Can, Too” and “The New Abolitionism: A Manifesto for a Movement”), the government of a free society should never be involved in educating children. The very idea is antithetical to a free society.

Sometimes it is said (falsely) that the purpose of government schooling is to teach children about the rights and virtues necessary for living in a free society, but this argument is self-evidently false. You can’t teach children about the principles necessary for living in a free society (e.g., rights and responsibilities) via an institution that violates those principles.

Over the course of the past 150 years, the specific ideological-political goals of government education have changed marginally with changing political administrations at both the state and federal levels, but the general goal of the government school system has remained the same: to separate children from the views of their parents and to mold them to the wishes of the State. In case you doubt this fact, consider the views of William H. Seawell, a professor of education at the University of Virginia, who defended government schooling by stating: “Each child belongs to the State.”[3]

In this fourth installment in our series, I would like to carry the story forward from the nineteenth into the twentieth century. The topic is, of course, worth a volume or two, but I shall spotlight how early twentieth-century intellectuals viewed the purposes of government schooling, and how and why they turned away in the 1920s and 1930s from the Prussian to the Bolshevik model as their source of inspiration. Seen in this light, we can better understand what government schooling in America is today.

Education by the State is Education for the State

By way of introduction, it is important to know that 1852 was the beginning of the end for education freedom in the United States. This was the year in which Massachusetts established America’s first ever system of comprehensive, statewide compulsory schooling. All children between the ages of eight and 14 were required to attend a government school no fewer than 13 weeks each year, unless exempted by attendance at a private school.

It should be noted, however, that not all residents of Massachusetts were happy with the government taking control of the education of their children. It is reported that approximately 80 percent of the residents of the Bay State opposed government schooling at the time, and in 1880 the state militia was called in to convince the parents of Barnstable (Cape Cod) to turn their children over to the State for their daily dose of indoctrination.[4]

Interrupted by the Civil War, the movement for compulsory government schooling picked up steam in the 1870’s and ‘80’s and was completed in the United States in 1918, when Mississippi, the last state, ended its system of education freedom and turned its children over to the government to be educated.

As we saw in my last essay on “Why Government Schooling Came to America,” nineteenth-century American proponents of government education used the Prussian model as their beau idéal. It wasn’t enough to mandate that children be educated in some way by parents (or their chosen surrogates), but they had to be educated by the State, which can mean only one thing: the State shall determine what children must learn, which means that, in a republican nation such as the United States, majority will (i.e., majority force) dictates what is to be taught and how it is to be taught. If you disagree and can’t send your child to a private or parochial school, you are out of luck.

Because government schooling laws are backed by the coercive force of the State via compulsory attendance laws and taxation (see what happens if your kids are truant from school or if you don’t pay your local property taxes), obedience becomes a primary requirement of citizenship. This is the logical, inevitable result of government schooling.

The Rise of Progressive Education

Once the system of government schooling was established in the United States by the early twentieth century, its proponents were then faced with the inevitable final battle—the battle against America’s parents for control of their children. This is what government schooling has always been about.

In his 1901 book Social Control, Edward A. Ross, a prominent American sociologist and education “reformer,” declared that the primary goal of government schooling “lies in the partial substitution of the teacher for the parents as the model upon which the children forms itself.” Government schooling, he continued, was “an engine of social control,” and to that end it should “collect little plastic lumps of human dough from private households and shape them on the social kneading-board.”[5]

And then there was Ellwood P. Cubberly, who went even further than Ross. Cubberly argued in his 1909 book Changing Conceptions of Education that the government school system must be viewed as a powerful tool of the State and that twentieth-century government schooling must be “paternalistic, perhaps even socialistic, in the matter of education,” and that with each passing year the child must come “to belong more and more to the state, and less and less to the parent.”[6]

Likewise, George S. Counts, a leading Progressive-socialist educator, insisted that children be liberated from “the coercive influence of the small family or community group.”[7] The real purpose of separating children from their parents was to prepare the way for remaking society along socialist lines.

In his 1932 manifesto Dare the School Build a New Social Order? Counts encouraged teachers and the Education Establishment to seek power for the purpose of transforming America from a capitalist nation (with property rights, profits, division of labor, supply and demand, competition, and prices) to a socialist nation (with collective owners ownership of natural resources, capital, and the means of production and distribution). Teachers were to be the vanguard of the revolution:

To the extent that they [teachers] are permitted to fashion the curriculum and procedures of the school, they will definitely and positively influence the social attitudes, ideals and behavior of the coming generation. . . . It is my observation that the men and women who have affected the course of human events are those who have not hesitated to use the power that has come to them.[8]

Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, Progressive educators urged America’s schools to take the lead in planning and creating a new social order. Their immediate goal was to remake the nation’s schools in order reconstitute American society. These Progressive educators (largely connected with the Teachers College of Columbia University) sought to replace individualism with collectivism, the rule of law with the rule of social engineers, laissez-faire government with bureaucratic central planning, and capitalism with socialism.

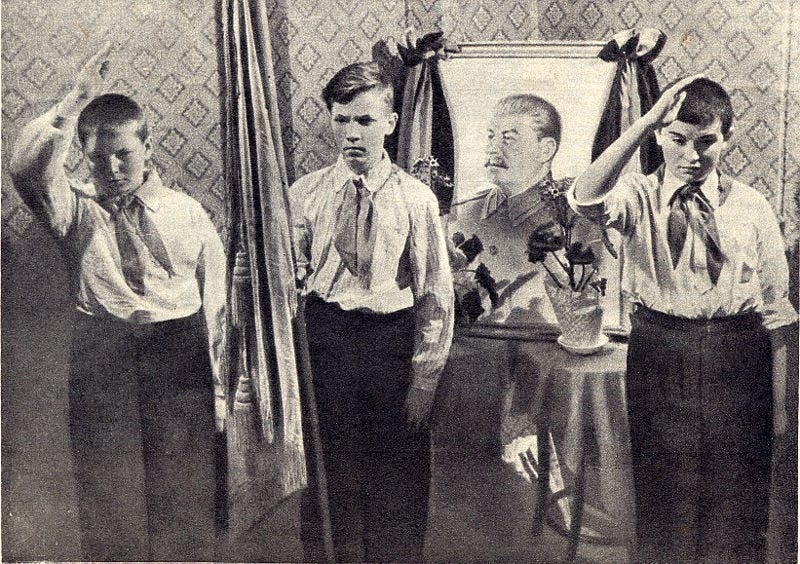

From Prussian to Bolshevik Schooling

The great philosophic doyen of Progressive-socialist education was John Dewey, who took his views on “reforming” American education from his friends in the Soviet Union. He praised Soviet educators for their discovery that school and State must work together to advance the socialist new frontier. The Bolshevik model of education, Dewey wrote, “is enough to convert one to the idea that only in a society based upon the cooperative principle can the ideals of educational reformers be adequately carried into operation.”[9] Dewey was a thoroughgoing collectivist-statist, who called for the creation of a powerful, centralized, state-controlled education system in order to advance the socialist ideal.

Proper education, Dewey wrote, “is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method social reconstruction.” The ultimate purpose of government schooling, according to Dewey, was to train children for the coming socialist society. Dewey was very clear about the outcomes he sought: “The social organism through the school, as its organ, may determine ethical results. . . . Through education society can formulate its own purposes, can organize its own means and resources, and thus shape itself with definiteness and economy in the direction in which it wishes to move.”[10]

Progressives believed that twentieth-century schools should replace nineteenth-century churches as the primary character-forming and culture-forming institutions of the new socialist society. For Dewey, the schools were to be secularly sacred institutions as was the role of teachers in the coming-into-being of the socialist utopia: “The teacher always is the prophet of the true God and the usherer-in of the true Kingdom of God.” A new generation of teachers would, Dewey wrote, make “schools active and militant participants in creation of a new social order.”[11] Socialism was the new social order of which Dewey spoke.

As should be absolutely clear to you by now, America’s government schools were, from Day One, created for political purposes. There is no getting around this fact. It was true in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and it’s true today. Thus it ever was and ever will be.

[1]. Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (London: John Chapman, 1851; republished New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, 1970), 297.

[2]. John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, ed. Currin V. Shields (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing,1956), 129.

[3]. Quoted in Sheldon Richman, Separating School & State (Fairfax, VA: Future of Freedom Foundation, 1994), p. 51 (emphasis added).

[4]. John Taylor Gatto, Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2002), 22.

[5]. Edward A. Ross, Social Control: A Survey of the Foundations of Order (New York: MacMillan Co., 1901), 164, 167-68.

[6]. Ellwood P. Cubberly, Changing Conceptions of Education (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1909), 61-63.

[7]. Counts quoted in Herbert M. Kiebard, The Struggle for the American Curriculum (New York: Routledge, 1995), 161.

[8]. George Counts, Dare the School Build a New Social Order? (New York: John Day, 1932), 28-29.

[9]. John Dewey, John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-1953, vol. 3: 1927-1928, ed. Jo. Ann Boydston (Carbondale, Ill: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 233-34.

[10]. John Dewey, “My Pedagogic Creed,” School Journal vol. 54 (January 1897), pp. 77-80.

[11]. John Dewey, My Pedagogic Creed,” School Journal vol. 54 (January 1897), pp. 77-80; “Can Education Share in Social Reconstruction,” in John Dewey: The Political Writings (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1993), 128.

I've been told that the Teachers accreditation association for Montessori Teachers, based in Colorado, has been taken over by CRT advocates. These advocates have banned people from speaking at meetings who disagree with them and their collectivistic philosophy of "social justice", never mind the idea of independent thinking and a free individual.

"These Progressive educators (largely connected with the Teachers College of Columbia University) ". It's no coincidence that Columbia University was also the birthplace of The Frankfurt School which brought cultural Marxism to America in the 1930s.