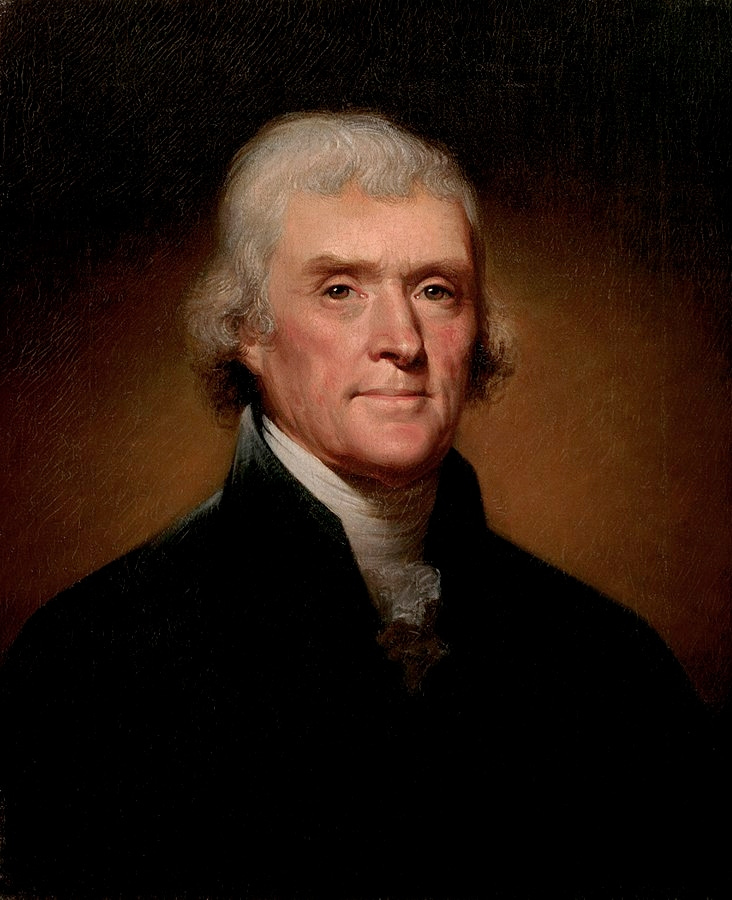

Thomas Jefferson and the Meaning of Self-Government

During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, America’s Founding Fathers and their political progeny began to think seriously about the kind of society they wanted to live in, not just politically but socially and economically as well. They viewed politics not as an end in itself, but as a means for creating a free society and living well.

At the political or macro level, the Founding generation had successfully fought a war for independence against the world’s strongest military force; they had created new governments at the state level; they had framed and ratified a national constitution; and they had launched their first national government. At the subcutaneous or micro level, a new kind of society was also emerging out of America’s revolutionary ferment. Even before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, John Adams saw and predicted the effects of a social revolution that was occurring just beneath the surface of American society:

The Dons, the Bashaws, the Grandees, the Patricians, the Sachems, the Nabobs, call them by what Name you please, Sigh, and groan, and frett, and Sometimes Stamp, and foam, and curse—but all in vain. The Decree is gone forth, and it cannot be recalled, that a more equal Liberty, than has prevail’d in other Parts of the Earth, must be established in America. That Exuberance of Pride, which has produced an insolent Domination, in a few, a very few oppulent, monopolizing Families, will be brought down nearer to the Confines of Reason and Moderation, than they have been used.

A year later, Thomas Jefferson, no less amazed at what he was seeing than Adams, told Benjamin Franklin that a radical transformation was taking place in American society, that “the people seem to have deposited the monarchical and taken up the republican government with as much ease as would have attended their throwing off an old and putting on a new suit of clothes.” In addition to this republicanization of American society in the original thirteen states was the equally transformative movement of tens and then hundreds of thousands of Americans and recent immigrants who were about to pour over the mountains for the trans-Appalachian West.

Out of the Revolution and the Founding emerged not just a new political order but a new social order and then a new order of men. Within a generation, the Founders’ powdered hair and knee breeches were gone. A new generation of leaders was beginning to emerge in the United States who were now prepared to dissolve, in Thomas Jefferson’s words, the last remnants of America’s “hereditary high-handed aristocracy,” which had, he noted, “by accumulating immense masses of property in single lines of a family divided our citizens into two distinct orders of nobles and plebeians.” The new men who were ascending to positions of political power first at the state level and then later at the national level were coming from the yeoman farmer class and city mechanics and were “not so well dressed, nor so politely educated, nor so highly born.” These new men wore clothes in a plain-dress style and were likewise plain in manner and speech. One effect of the Revolution was to democratize American culture by downgrading aristocratic pretensions for republican forms and formalities.

An old era was about to die, and a new one was about to be born. Beginning in the 1790s, the American people now had the opportunity to extend their republican experiment from the realm of philosophy and politics down to the social and economic levels.

The Second American Revolution

In a 1798 letter to John Taylor of Caroline, Thomas Jefferson predicted that the Federalist “reign of witches”—i.e., the reign of the Federalists—would soon end, and the good people of the United States would return their government to America’s “true principles.” Jefferson’s prophecy was fulfilled two years later when he was elected President of the United States and his Republican Party swept both houses of Congress.

Writing to Spencer Roane in 1819, Jefferson described the presidential election of 1800 as a revolution in the principles of American government, “as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 76.” Jefferson’s meaning was clear: the election of 1800 represented a second American Revolution—a revolution not to overturn the first one but to apply its principles to new realms of living. Converting theory into practice is always the hard part.

There may be a degree of conceit or self-promotion in Jefferson’s claim about the importance of his election (a claim not uncommon for many presidents), but its veracity is not far off the mark. The election of 1800 had a double meaning for Jefferson: it was both backward- and forward-looking. It represented a return to first principles, and it projected a new future for America. Whereas 1776 represented a revolution in moral and political principles, 1800 represented the practical implementation of those principles in the social and economic spheres. This second revolution was a watershed moment in American politics and society.

In its wake, the Federalist Party was virtually dead by the end of the War of 1812, leaving the Jeffersonian philosophy of government to reign supreme for at least another generation. As a result, American society was about to be revolutionized. The Virginian’s election and reelection in 1804 followed by those of James Madison and James Monroe for another 16 years defined a new age of politics for the new nation. Except for John Quincy Adams’s interregnum presidency from 1825 to 1829, one could reasonably claim that the reign of Jefferson’s second American revolution extended through the administrations of Andrew Jackson (1829-1837) and Martin Van Buren (1837-1841).

The Meaning of the Revolution of 1800

What was so important, indeed, so revolutionary, about Jefferson’s election? Why did he think it represented a second American revolution? What affect did his election have on American life and culture?

To start with, Thomas Jefferson’s election to the presidency in 1800 along with his fellow Republicans sweeping both houses of Congress represented a rejection of the principles and policies of monarchy and aristocracy (or, at least, so Jefferson claimed), which the new president identified with the Federalist party leadership. But there was a deeper meaning to the election of 1800 than just what was being rejected. The Jeffersonians projected a view of republican self-government that was more than just a philosophy of political institutions. It was a moral, social, and economic philosophy as well—a philosophy that believed in man’s ability to govern himself largely without government. Ultimately, it was a philosophy about how men should live.

Late in his life, Jefferson summed up what he took to be the three major philosophic differences between the Federalists and the Republicans.

First, he wrote, “We believed . . . that man was a rational animal, endowed by nature with rights, and with an innate sense of justice, and that he could be restrained from wrong, & protected in right, by moderate powers, confided to persons of his own choice, and held to their duties by dependance on his own will.”

Second, “we believe that the complicated organisation of kings, nobles, and priests was not the wisest nor best to effect the happiness of associated man; that wisdom and virtue were not hereditary; that the trappings of such a machinery consumed, by their expence, those earnings of industry they were meant to protect, and, by the inequalities they produced, exposed liberty to sufferance.”

And finally, “We believed that men, enjoying in ease and security the full fruits of their own industry, enlisted by all their interests on the side of law and order, habituated to think for themselves and to follow their reason as their guide, would be more easily and safely governed than with minds nourished in error, and vitiated and debased, as in Europe, by ignorance, indigence and oppression.”

What Jefferson was here identifying surely represents a philosophic, political, and social revolution in the affairs of men. When and where in human history had philosophers, political founders, rulers, and statesmen viewed man’s nature as rational, volitional, rights-bearing, and capable of self-government in the fullest sense of the term? No such time or place had exited but for the American experiment in self-government launched at the end of the eighteenth century.

If 1776 symbolized what John Adams once referred to as a revolution in moral and political principles, then the election of 1800 represented a socio-economic revolution, the purpose of which was to implement politically the moral principles of 1776 such that they would bear fruit in the social and economic realms. The moral-political principles of 1776 were, of course, summed up in the four self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence, which stated:

that all men are created equal,

that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

To better understand the nature and meaning of Jefferson’s second American Revolution, we should focus on the third self-evident truth, which represents the transition between morality and politics. The Declaration’s third truth states that the purpose of government—the sole purpose—is to secure the inalienable rights listed in the second self-evident truth (i.e., the protection of man’s inalienable rights).

This means that the purpose of government in a free society is not to make men virtuous or equal. Instead, its purpose is to leave them alone, to adjudicate justice between them, and to protect them from violence domestic and foreign. In other words, the ideal form of government for Jefferson and the Republicans was republican self-government, which Jefferson understood in the most radical sense.

Self-Government—American Style

At the heart of the Jeffersonian definition of a free society was the idea of self-government. A free society was a self-governing society, which, in the fullest sense of the term, meant that individuals were not only free to govern themselves, but they were expected to do so. The idea of individual self-governance meant the right and the good of individuals to guide their own lives and to forge their own destinies according to their own rational faculties and a moral code grounded in nature or reality.

Not only was the Jeffersonian theory of self-government a moral imperative for all Americans, but it was also a social reality for many Americans (e.g., those living on the frontier), who were forced of necessity to govern themselves entirely without government, or at least with not much government most of the time. This meant that men had the capacity to govern themselves and that they should do so. “My hope,” Jefferson wrote to George Mason in 1791, is “that our experiment will still prove that men can be governed by reason.” Thirteen years later, the Virginian was convinced that the experiment had succeeded and had proved to the world “the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth.” Jefferson believed that man’s capacity for self-government was grounded in the fact that all men have the necessary reason to live their lives independent of meddling government officials. When governed by reason and truth, Jefferson was certain that “men are capable of governing themselves without a master.”

The idea and practice of self-government required certain social-political conditions, namely, the institutionalization of freedom, rights, and justice. The Jeffersonian idea of a free, self-governing society was premised on the “equal rights of man” and “the happiness of every individual” as the “only legitimate objects of government.” This meant that freedom must be protected and institutionalized. To that end, the social and economic relations between the individuals of society were to be governed by established cultural manners and mores and by a system of natural and conventional justice, the purpose of which was to protect the rights of men as individuals. In other words, not only can men be left alone, but they also actually live better and more virtuous lives.

Post-Founding Americans developed and put into practice a revolutionary theory about government and governing and life and living. If individuals can govern themselves and should be responsible for doing so, then they must be left alone and not ruled by rulers. They must learn to rule themselves. Thus, the election of 1800 ushered in what we might designate as “The Age of Laissez Faire,” or, more precisely, “The Age of Laissez-Faire Government.”

As I’ve noted elsewhere, I use the term “laissez faire” differently than most scholars, who mostly use it to refer to economics or the economic realm. By contrast, I use “laissez faire” to refer to government and government policy. The term laissez faire (variously translated as “let it happen,” “let be,” or “let do”) is a principle in the form of a commandment, which is directed not at individuals but at government officials. The commandment instructs legislators and bureaucrats to not interfere with various forms of what should be private human actions, such as economic, education, or religious activities. In other words, the idea of laissez faire is a political philosophy with policy implications for society, culture, religion, and economics.

The laissez-faire political philosophy, certainly in its American context, begins constitutionally and politically with a distrust of political power and the need to control it with a written constitution.

Jefferson was not, as he told Madison in 1787, “a friend to a very energetic government,” and he told a French correspondent that same year that the policy of the United States should be “to leave their citizens free, neither restraining nor aiding them in their pursuits.” Self-government meant freedom from rights-violating government officials.

The clearest expression of Jefferson’s laissez-faire constitutionalism can be found in the ninth of his Kentucky Resolutions, which he drafted in 1798. “Free government,” the Virginian wrote, “is founded in jealousy and not in confidence; it is jealousy and not confidence which prescribes limited Constitutions to bind down those whom we are obliged to trust with power.” The great virtue of the America’s laissez-faire Constitution, he continued, was that it “has accordingly fixed the limits to which and no further our confidence may go.” When it came to “questions of power,” Jefferson was not willing to settle for a “confidence in man.” He had confidence in men to govern themselves but not to govern others. Instead, all rulers should be bound “from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.”

Laissez-Faire Society and Self-Government

Jefferson’s philosophy of laissez-faire government understood individual freedom and self-government not as a threat to the social order but rather as the cultural glue holding a free society together. According to Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, the core “social institutions” upholding a free society were “property and marriage,” while governments “founded on law” were the necessary condition “that might insure liberty, preserve order, and protect persons and property.” Leave men free to acquire property and families and the rest would pretty much take care of itself.

The Founding and post-Founding generations came to believe that social cohesion, loyalty, and patriotism must not and could not be achieved though State coercion but only through the natural system of liberty and the natural social order. In other words, self-government was the vehicle through which the natural order of freedom and justice would achieve order and equilibrium. A society of free, self-governing individuals would largely take care of itself, and if the powers of each member were insufficient to supply for their individual needs, they would seek out and trade with others in voluntary exchanges of goods and services and they could join with others in associations to achieve common goods.

In the Jeffersonian world, self-government meant government intervention would be minimized to encourage free-market relations in social, religious, and economic affairs. Society and economy would be coordinated and harmonized by supply-and-demand, the price mechanism, and profit-and-loss, which applied to social relations no less than it did to economic relations. Jeffersonian Republicans believed that a free society organized by the market could become the centripetal force uniting America in a system of voluntary commercial and social relations. Only then would it be possible for men to be moral and to live together in social harmony. Instead of social order forming unnaturally at the behest of top-down government diktats, Jefferson believed that it would form naturally from the bottom up if only government got out of the way other than to provide for a system of justice and common defense.

President Jefferson understood that the American experiment in self-government was also an experiment and test case for the rest of the world. The American people, he told the English philosopher Joseph Priestly in 1802, are “wise, because they are under the unrestrained and unperverted operation of their own understandings.” Jefferson understood the trans-historical nature of the American experiment in republican self-government:

A nation composed of such materials, and free in all it’s members from distressing wants, furnishes hopeful implements for the interesting experiment of self-government: and we feel that we are acting under obligations not confined to the limits of our own society. It is impossible not to be sensible that we are acting for all mankind: that circumstances denied to others, but indulged to us, have imposed on us the duty of proving what is the degree of freedom and self-government in which a society may venture to leave it’s [sic] individual members.

Three years later in his Second Inaugural Address, Jefferson noted that it had been reserved to the American people to determine “whether freedom of discussion, unaided by power, is not sufficient for the propagation and protection of truth: whether a government conducting itself in the true spirit of its constitution with zeal and purity and doing no act which it would be unwilling the whole world should witness can be written down by falsehood and defamation.” America was a model of self-government for the rest of the world. The forces of nature and philosophy had conspired to create the conditions necessary for success. If the American experiment were to fail, surely it would fail everywhere else. The experiment, he continued, had been a stunning success. At the moment of greatest peril, the American people “gathered around their public functionaries, and when the Constitution called them to the decision by suffrage, they pronounced their verdict, honorable to those who had served them and consolatory to the friend of man who believes he may be intrusted with his own affairs.”

Deconstructing Government

This laissez-faire relationship between government and society found its classic American expression in Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address. There the new president of the United States announced the republican philosophy of political liberalism and self-government that would guide his administration and those of his successors for another generation or so. Jefferson equated legitimate and good government with the declaration and enforcement of natural justice, which he equated with the protection of man’s natural and civil rights.

The third president defined the moral principles that should guide men in their actions and in their relations with each other as threefold: first, to recognize “a due sense of our equal right to the use of our own faculties”; second, to recognize our equal right “to the acquisitions of our own industry,” and third, to recognize our equal right to “honor and confidence from our fellow-citizens, resulting not from birth, but from our actions and their sense of them.” Jefferson believed that these three moral principles were the glue that would hold together his Arcadian Utopia.

Broadly speaking, Jefferson’s ideal form of government was, as he famously said in his First Inaugural, “wise and frugal” and which “shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.” This is the very definition of self-government.

Jefferson then laid out sixteen “essential principles of our government, and consequently those which ought to shape its administration”:

Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political;

peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none;

the support of the State governments in all their rights, as the most competent administrations for our domestic concerns and the surest bulwarks against antirepublican tendencies;

the preservation of the General Government in its whole constitutional vigor, as the sheet anchor of our peace at home and safety abroad;

a jealous care of the right of election by the people—a mild and safe corrective of abuses which are lopped by the sword of revolution where peaceable remedies are unprovided;

absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority, the vital principle of republics, from which is no appeal but to force, the vital principle and immediate parent of despotism;

a well-disciplined militia, our best reliance in peace and for the first moments of war till regulars may relieve them;

the supremacy of the civil over the military authority;

economy in the public expense, that labor may be lightly burthened;

the honest payment of our debts and sacred preservation of the public faith;

encouragement of agriculture, and of commerce as its handmaid;

the diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason;

freedom of religion;

freedom of the press;

freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus;

and trial by juries impartially selected.

These principles, Jefferson declared, “should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust.” This is what a laissez-faire government looked like for America’s Founders. Jefferson believed that a self-governing society would be a morally virtuous society because freedom provided its own school of citizenship. Freedom necessitated that such men be good and virtuous. The alternative was penury, failure, and social neglect.

Jefferson’s Laissez-Faire Government

Jefferson and his followers were, as we have demonstrated, proponents of limited—very limited—government. In addition to separating and dividing political power, Jefferson and his supporters believed in government economy at all levels, which largely meant two things: keeping taxes and the size of government to a minimum.

Once in office, the Jefferson administration began the process of putting into effect the long-held constitutional, political, and economic views of the new president. Almost immediately, Jefferson began dismantling Hamilton’s centralized, top-down fiscal program by freeing money and credit from national control, reducing taxes, and cutting the size of the civil service. As a result, there was an inverse relationship in early nineteenth-century America between the amount of coercive power used by government and the amount of freedom retained by the citizenry. As the Jeffersonians in power whittled away at the size and activities of the federal government, the spheres of freedom for American citizens increased.

Jefferson’s goal of deconstructing the Hamiltonian Deep State reached its climax in his First Annual Message to Congress, delivered on December 8, 1801, where he said, “there is reasonable ground of confidence we may now safely dispense with all the internal taxes, comprehending excise, stamps, auctions, licenses, carriages, and refined sugars.” President Jefferson reminded Congress that “this government is charged with the external and mutual relations only of these states; that the states themselves have principal care of our persons, our property, and our reputations, constituting the great field of human concerns.” With those ends in mind, Jefferson went on to say that the American people “may well doubt whether our organization is not too complicated, too expensive; whether offices and officers have not been multiplied unnecessarily, and sometimes injuriously to the service they were meant to promote.” And with both houses of Congress under Republican control, Jefferson was also able to reduce the military establishment by slashing army and naval appropriations. As a result, the army was reduced to two regiments of infantry and one of artillery.

Jeffersonian-style government was lean and austere. Consider one data point. In 1801, at the beginning of the Jefferson presidency, the United States Department of Treasury had 1,285 employees; a quarter of a century later, at the end of James Monroe’s two terms in office, there were just 1,075 employees of the Treasury department. Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, reduced the debt of the United States from $80 million to $57 million, and he created a surplus of $14 million.

The Jeffersonians’ fear of government was virtually instinctual, and they came as close as anyone in history ever has to propounding a policy of absolute or pure laissez faire grounded on the axiomatic principles of the right of men to self-government, to freedom, and to keeping the fruits of their labor. They wanted to chain down government as the Lilliputians chained down Gulliver to prevent its genetic predisposition toward behemothism.

Jefferson and his followers wanted government at all levels to be small, frugal, and efficient. They wanted a government largely unheard, unseen, and unfelt. During his first year in office, Jefferson told a correspondent that he wanted his administration to run a federal government as though by stealth. “The path we have to pursue is so quiet,” he continued, “that we have nothing scarcely to propose to our legislature.” The best kind of government is one that pursues “a noiseless course” and [not] medling with the affairs of others.”

In his First Inaugural, Jefferson was speaking of the role that the national government should play in American society. President Jefferson limited the function of the federal government to a handful of tasks for which only a national government could be responsible, and he divided all other necessary functions to state and local governments. Imbedded in his view of America’s laissez-faire Constitution was a core principle that we might call “muscular federalism,” or the view that political power should be divided into different levels of government and eventually most political power would be imploded through several layers of government right down to the individual level.

Twenty-three years after he delivered his First Inaugural and two years before he died, Jefferson explained precisely what he meant by the principle of federalism and the powers appropriate to each level of government in a fascinating letter to Joseph C. Cabell in 1823. The former president was certain that “the way to have good and safe government, is not to trust it all to one; but to divide it among the many, distributing to every one exactly the functions he is competent to.” He continued:

Let the National government be entrusted with the defence of the nation, and it’s foreign & federal relations; the State governments with the civil rights, laws, police & administration of what concerns the state generally; the Counties with the local concerns of the counties; and each Ward direct the interests within itself. It is by dividing and subdividing these republics from the great National one down thro’ all it’s subordinations, until it ends in the administration of every man’s farm and affairs by himself; by placing under every one what his own eye may superintend, that all will be done for the best.

Federal, state, county, and ward governments would assume those political powers appropriate to their natural jurisdiction and competency, but ultimate power should rest on the moral and political sovereignty of each individual as governs himself on his own farm. This is what Jefferson meant by self-government, at least politically.

Lastly, the proponents of laissez-faire government did not think that politicians and bureaucrats should view their positions as a species of personal property. Self-government did not mean pursuing government bounty for one’s own reward. Twenty-eight years after Jefferson ascended to the presidency, newly elected President Andrew Jackson warned the men then sitting in the House of Representatives that they should not use their office as a vehicle to serve their private interests. To that end, he proposed in his First Annual Message that they consider an amendment to the Constitution that would limit their term of office to four years. Nor did Jackson think the qualities necessary for a political night-watchman required any special talents. President Jackson then identified and downgraded the requirements to serve in the government of the United States: “The duties of all public officers are, or at least admit of being made, so plain and simple that men of intelligence may readily qualify themselves for their performance.” It turns out that government and politics are not that difficult if left to their proper functions.

Conclusion

In sum, Jefferson and two generations of his followers supported a strict separation between the economy and the State such that government would be reduced to its legitimate but minimal protecting the rights to liberty and property, thereby creating the space for the harmonious workings of a market society where wealth could be produced, traded, and accumulated without government interference.

At the center of Jefferson’s political economy was the belief that all forms of economic production and trade (e.g., “Agriculture, manufactures, commerce and navigation,” which he called “the four pillars of our prosperity”) “are the most thriving when left most free to individual enterprise.” Albert Gallatin, Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, told his boss in 1801 that there was a cause-and-effect relationship between limited government and wealth creation. Republican governments based on “those republican principles of limitation of power & public economy” were the cause of wealth creation, which, he told Lafayette years later was “always eminently increased under governments which, abstaining from the exercise of every species of arbitrary power, govern by equal laws and, without favoring or oppressing any particular class of people or species of occupation, afford complete security to persons, industry, and property.”

The political-economic-social theory of laissez faire was critical for the realization of a free society grounded in man’s individual rights and the self-ordering mechanisms of the market. Freedom was the necessary ingredient in creating a natural social order that would forge common bonds tied together by complementary human needs and wants.

***A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.

Thomas Jefferson, not surprisingly, was the most important interpreter of his own work in his famous May 8th 1825 letter to Richard Henry Lee:

"This was the object of the Declaration of Independance. not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject; [. . .] terms so plain and firm, as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independant stand we [. . .] compelled to take. neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the american mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. all it’s authority rests then on the harmonising sentiments of the day, whether expressed, in conversns in letters, printed essays or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney Etc."

I'm sure you're incredibly busy, but if you ever thought of doing requests, I'd love to see something on Washington's farewell address and principles of foreign intervention, since it's such a hot issue right now (Ukraine/Israel).