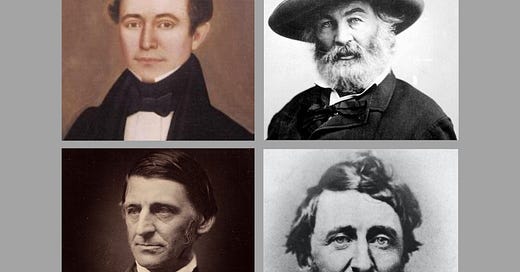

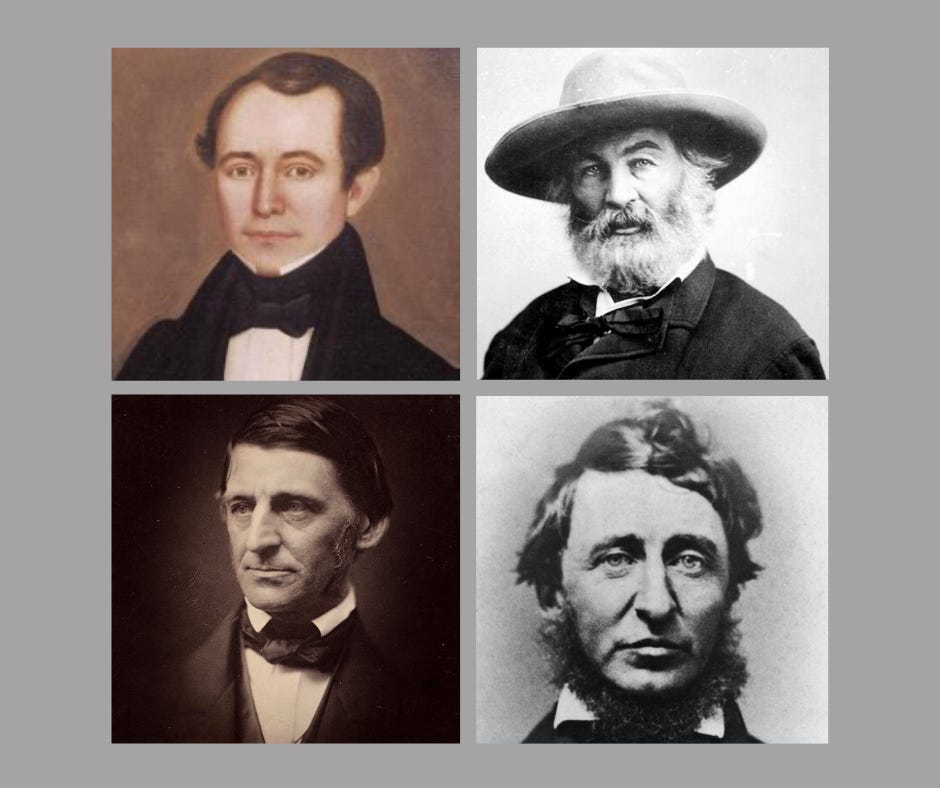

In 1850, Ralph Waldo Emerson (pictured bottom left) published a book of essays titled Representative Men. Emerson’s title seems appropriate for this essay of mine as it is meant to elucidate, in part, the philosophical and political views of four representative men (i.e., William Leggett, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau)—men who were representative of the views of many Americans in antebellum America and, more broadly, of what I have referred to elsewhere as the philosophy of Americanism.

In a previous essay, “Regime Change, American Style,” I examined the kind of society that the founders rejected and the new kind of political order they created for the future. Then, in “‘Leave Us Alone’ as a Political Philosophy,” I explored how the first two generations of post-founding Americans understood and implemented the founders’ political philosophy. The most uniquely American political philosophy that came out of the founding era could be summed up in the well-known phrase: “The best government is that which governs least.” No other nation in world history was governed by such a political philosophy. The founding generation, and certainly their progeny, were believers in limited government because they were believers in self-government.

The political opinions of antebellum Americans expressed in “‘Leave Us Alone’ as a Political Philosophy” were not those of a radical fringe; these ideas were commonly accepted by a broad cross-section of American society, including some of nineteenth-century America’s best known public intellectuals.

In this essay, I would like to drill down a bit and consider the views of four of America’s most famous nineteenth-century proponents of a laissez-faire government and a free society: William Leggett (1801-1839), Walt Whitman (1819-1892), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). I will also consider how pre-Civil War Americans understood the relationship between government and legislation in a free society.

William Leggett, editor of the highly influential Evening Post in New York City, was the intellectual leader of the so-called Loco-Foco movement, which was a radical workers’ faction of the Democratic Party in New York City dedicated to laissez-faire politics and economics during the 1830s and 1840s. Leggett and the Loco-Focos, based on their understanding of the moral principles of the American founding (i.e., the doctrine of individual rights), attempted to develop a political philosophy consistent with their underlying moral principles. Not surprisingly, they advocated for a night-watchman government that was limited to protecting the equal rights of all men.

In an 1834 op-ed on the “True Functions of Government,” Leggett, applying the third self-evident truth of the Declaration of Independence to the politics of the 1830s, announced the “fundamental principle of all governments is the protection of person and property from domestic and foreign enemies.” Beyond these basic purposes, the government of a free society shall not go. Otherwise, society and the individuals that made it up would not be free.

So, what then shall government do in a free society? According to Leggett, the sole “functions of government, when confined to their proper sphere of action, are therefore restricted to the making of general laws, uniform and universal in their operation, for these purposes and for no other.”

Leggett was also clear as to what the government of a free society must not do.

A laissez-faire government has, Leggett argued, “no right to interfere with the pursuits of individuals, as guaranteed by those general rules,” nor does it have a right “to tamper with individual industry a single hair’s breadth beyond what is essential to protect the rights of person and property.” Free men should be left alone, he continued, from the “capricious interference of legislative bungling.” The government of a free society should never be given or assume the power to discriminate, Leggett wrote, “between the different classes of the community,” to be the “arbiter of their prosperity,” or to regulate the “profits of every species of industry.” Such a government “reduces men from a dependence on their own exertions to a dependence on the caprices of their government” and is therefore immoral.

Walt Whitman, once described by Ezra Pound, as “America’s poet,” was a principled proponent of limited government and a free society mostly because he was, more than anything else, a believer in the proposition that man has a right to govern himself. In an 1847 essay titled “The Best Government is That Which Governs Least,” Whitman announced that “Men must be ‘masters unto themselves,’ and not look to presidents and legislative bodies for aid.” He did not think that government could do much “positive good” for men; indeed, he thought it likely that government “may do an immense deal of harm.” Thus, the only form of good government was one that served, he wrote in an essay titled “Government No Meddler,” as a “prudent watchman,” which would “make no more laws than those useful for preventing a man or body of men from infringing on the rights of other men.” In other words, the laws of a free society should be “few, simple, and general,” wrote Whitman in an essay “On Compulsion in Government.

In his essay on “Politics” published in 1849, Ralph Waldo Emerson, probably America’s best-known nineteenth-century public intellectual, denounced government and politics as inherently corrupt and corrupting. “Every actual State is,” he fumed, “corrupt,” and the history and nature of governments can be summed up, he wrote, with a simple formula: “A man who cannot be acquainted with me, taxes me: looking from afar at me ordains that a part of my labor shall go to this or that whimsical end.” Thus, his admonition to “good men” was that they “must not obey the laws too well.”

Emerson’s ultimate position on the relationship between the individual and government summed up the views of an entire generation: “Hence the less government we have the better,—the fewer laws, and the less confided power. The antidote to this abuse of formal government is the influence of private character, the growth of the Individual.” The social philosophy of antebellum northern society could be summed up, Emerson claimed, in two related concepts: individualism and “the idea of self-government,” which meant to “leave the individual . . . to the rewards and penalties of his own constitution.”

Henry David Thoreau, Emerson’s close friend and fellow anti-statist, was even more adamant in his defense of individualism and obstinate in his contempt for the State. (I define “The State” as that form of government that has exceeded its legitimate functions.)

Thoreau began his 1849 essay “Resistance to Civil Government” with jarring words that echoed the Jeffersonian principle: “I heartily accept the motto, ‘That government is best which governs least.” To be outdone only by himself, Thoreau then went further and declared, “That government is best which governs not it all.” To be clear, Thoreau was not an anarchist. He believed that the proper function of government was to adjudicate justice and to protect the citizenry from force and fraud. He did not believe that the role of government was to “govern,” which is something more. Thoreau understood that a proper government—the government of a free society—does not further “enterprise,” “keep the country free,” “settle the West,” or “educate” the young. Individuals or voluntary associations of individuals can and should do those things on their own.

The best government, according to the hermit of Walden’s Pond, was that which gets out of the way and leaves men alone. If nothing else, Thoreau carried the vision of laissez-faire government to its logical if not its beautiful conclusion:

There will never be a really free and enlightened State, until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at last which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose, if a few were to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men.

The founding fathers would have been proud of their intellectual and political progeny. Living up to the standards of what was truly “The Greatest Generation” was no small task, but many of the founders’ sons and grandsons did an admirable job of completing America’s experiment in self-government.

Anti-Legislation

Still, even though virtually all antebellum Americans believed in theory that the purpose of government was to protect man’s rights, far too many were either unwilling or incapable of putting their ideals into practice. In other words, some Americans did not understand the necessary relationship between theory and practice and some were simply not willing or able to live according to their avowed principles.

This problem was not, of course, unique to antebellum America. The truth is that men from time immemorial and forever, men have struggled to live according to their principles. It is an all-too-common truism of the pragmatist mentality to assert that a particular principle might be true in theory cannot be reduced to practice.

This kind of anti-principle attitude was the great problem confronted by the proponents of America’s laissez-faire Constitution. As William Leggett put it in an 1837 editorial for the Plaindealer, “The principle of man’s natural and unalienable equality of rights is admitted in the abstract, but is widely departed from in practice.” Thus, it was absolutely necessary for the true proponents of a free society to unite theory and practice and to live out their principles in practice. In an editorial on “Theory and Practice,” Leggett announced the great challenge of his time: “Whatever is true in theory it is our duty to reduce to practice; for the great end of human effort is the accomplishment of truth.”

Not surprisingly, it turns out that it’s not enough to have the right theory. The real challenge is to be true to one’s moral principles in practice.

Those Americans who supported the founders’ Constitution throughout the nineteenth century understood the need for integrity and consistency in politics. They took seriously the need to integrate theory and practice. The founders’ true nineteenth-century heirs were principled proponents of the need to be principled, which meant that a “wise, prudent, and virtuous people” must, “in order to continue free,” according to Stephen Simpson, “never lose sight of principle.”

The principle that antebellum Americans took most seriously was, in theory at least, the idea that the sole purpose of government in a free society is to protect the equal rights of individuals. Full stop. Beyond that, it shall not go.

So, what does the protection of individual rights and the idea of self-government mean in practice? How does it cash out politically?

According to Gilbert Vale, it means “these principles lead generally to a negative, rather than to a positive” view of legislation, which in turn means that laws should “be prohibitory of individuals invading the natural rights of others” and such laws would “impose penalties on such violations.” Vale characterized positive law as that form of legislation that is tantamount to what he called “club law,” which in effect defines justice and the rule of the stronger.

The great problem of politics was, is, and always will be the inherent tendency of some human beings to seek power, either for power’s sake and the pleasure derived by some for commanding other people how to live or to acquire wealth, status, and influence.

In the American context, President Andrew Jackson warned his fellow Americans in his “Farewell Address” that there were men who seek the power to rule over fidelity to the Constitution. Jackson’s final words to the American people came in the form of a warning and a prophecy. The Constitution’s “legitimate authority is abundantly sufficient for all the purposes for which it was created; and its powers being expressly enumerated, there can be no justification for claiming anything beyond them.” Jackson then issued this warning to his countrymen:

Every attempt to exercise power beyond these limits should be promptly and firmly opposed. For one evil example will lead to other measures still more mischievous; and if the principle of constructive powers, or supposed advantages, or temporary circumstances, shall ever be permitted to justify the assumption of a power not given by the Constitution, the General Government will before long absorb all the powers of legislation, and you will have, in effect, but one consolidated government.

President Jackson, his successor Martin Van Buren, and their allies fought the designs of the political class to increase its power, influence, status, and wealth.

The history of government in America since the time of the founding was, according to William Leggett, a sordid tale demonstrating that “one of the great practical evils of our system arises from a superabundance of legislation,” which Leggett estimated to “amount to some thousands annually.” Leggett charged both federal and state legislatures with “regularly and systematically . . . frittering way, under a thousand pretenses, the whole fabric of the reserved rights of the people.” Leggett estimated that “[n]ine tenths” of all legislation passed in the United States in any given year has “consisted of infringements of that great principle of equal rights.” The special “vocation” of American legislators, he added, “has consisted not in making general, but special laws: not in legislating for the whole, but for a small part; not in preserving unimpaired the rights of the people, but in bartering them away to corporations.” By “special” laws, Leggett meant laws that discriminate for or against particular individuals or classes of people.

The Jacksonians battled the political entrepreneurs of their time who sought to “embrace a thousand objects which should be left,” according to William Leggett in an editorial on “The Morals of Politics,” “to the regulation of social morals and unrestrained competition, one man with another, without political assistance or check.” This kind of “special legislation,” he noted, “degrades politics into a mere scramble for rewards obtained by a violation of the equal rights of the people.” And in an editorial on “The Legislation of Congress,” Leggett further noted that the “present system of our legislation seems founded on the total incapacity of mankind to take care of themselves or to exist without legislative enactment.”

The solution to the problem was easy in theory, but unfortunately difficult in practice. The answer was, according to the Evening Post, to “confine government within the narrowest limits of necessary duties” and to disconnect the State from all functions that do not serve its purpose (i.e., the protection of equal rights).

What this meant in practice, first and foremost, is that the end or purpose of government is not to serve the so-called “public good,” which is an open-ended, undefinable, subjective, floating, fill-in-the-blank abstraction. The founding generation’s leading intellectual and political progeny understood that “there is no more effectual instrument of depriving” the American people of their equal rights “than a legislative body, which is permitted to do anything it pleases under the broad mantle of THE PUBLIC GOOD.”

The post-founding generation knew that the political idea of a “common good” or a “public good” means that governments may—indeed, it must—do anything in the service of its limitless end. As the Evening Post put it in an 1834 editorial, the idea of the “public good” will “become the mere creature of designing politicians, interested speculators, or crack-brained enthusiasts.” Thus it was, is, and always has been.

The equal rights principle and the rule of law taught Jacksonian-era Americans that government must not discriminate between citizens, benefitting a few at the expense of the many. This meant the founders’ true successors only considered a relatively small number of laws to be moral and just. A strong majority of post-founding Americans therefore supported getting government out of the affairs of men that could and should be done privately. In other words, they supported the strict separation of economy and State.

This meant in practice they opposed, among other things, exclusive, government-sponsored charters, monopolies, and privileges of all sorts (e.g., with regard to churches, schools, colleges, banks, ferries, mail delivery, etc.), government-funded internal improvements (e.g., canals, roads, railroads, etc.), regulations, subsidies, tariffs, all taxes exceeding the specific powers entrusted to government by the constitution, and wealth redistribution (e.g., poor laws) in all forms. In other words, those Jacksonian-era Americans who consistently applied the founders’ principles opposed “all Government stimulants” and what the Evening Post called the “force-pump method” of legislation and economic stimulation.

The founders’ nineteenth-century heirs—their true heirs—did not think it proper for government to dispense “favors to one or another class of citizens at will; of directing its patronage first here and then there; of bestowing one day and taking back the next; of giving to the few and denying to the many; of inventing wealth with new and exclusive privileges and distributing . . . in unequal portions, what it ought not to bestow or what, if given away, should be equally the portion of all.” In sum, they took seriously the Constitution’s prohibition against creating any kind of “Title of Nobility.”

Put differently, America’s nineteenth-century proponents of a free society supported free enterprise, free banking, free production, free trade, unrestricted competition, and charity. They were, in other words, the founders’ true inheritors, and they created the world’s first truly free and moral society.

My opinion of Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau just improved a thousand percent. I never knew anything about their political positions so am quite happy to find out such prominent men were fully on board with a laissez faire government. I had known generally (from Ayn Rand) that 19th Century America was the closest humanity had come to ever having a proper government, but this is terrific to get some history and details of just how the intellectuals and the people of that time thought about government and tried to put those thoughts into practice.

"Not Yours to Give" Davy Crockett's Speech before the House of Rep

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRFaGi2lqrY&t=311s&pp=ygUNZGF2eSBjcm9ja2V0dA%3D%3D