***I’m pleased to announce that I will be providing audio versions of my long-form essays for paid subscribers. I will link to the audio file at the end of each essay.

Freedom of commerce—which builds on the inviolability of private property and the sanctity of contracts—is the third principle of a free, just, and prosperous society. Commerce is what inevitably happens when private property is protected, contracts enforced, and people are left alone to produce and trade. These three core principles of a free society are related to each other in a chronological and hierarchical relationship, and they work together in harmony to produce a society that is just, prosperous, and benevolent. Commerce is enhanced by contracts, and contracts are built in turn on private property. As with contracts and property, commerce requires maximal freedom to flourish.

Broadly speaking, this essay examines what commerce is, how it arises, and why it is necessary for human flourishing. More specifically, as with my previous essays on private property and contracts, this essay examines the rise of commerce in its American context, particularly in the light of the American Founding. I will focus here on the political economy of commerce rather than on its underlying economic principles (e.g., division of labor, supply and demand, comparative advantage, prices, diminishing marginal utility, competition, and profit, etc.).

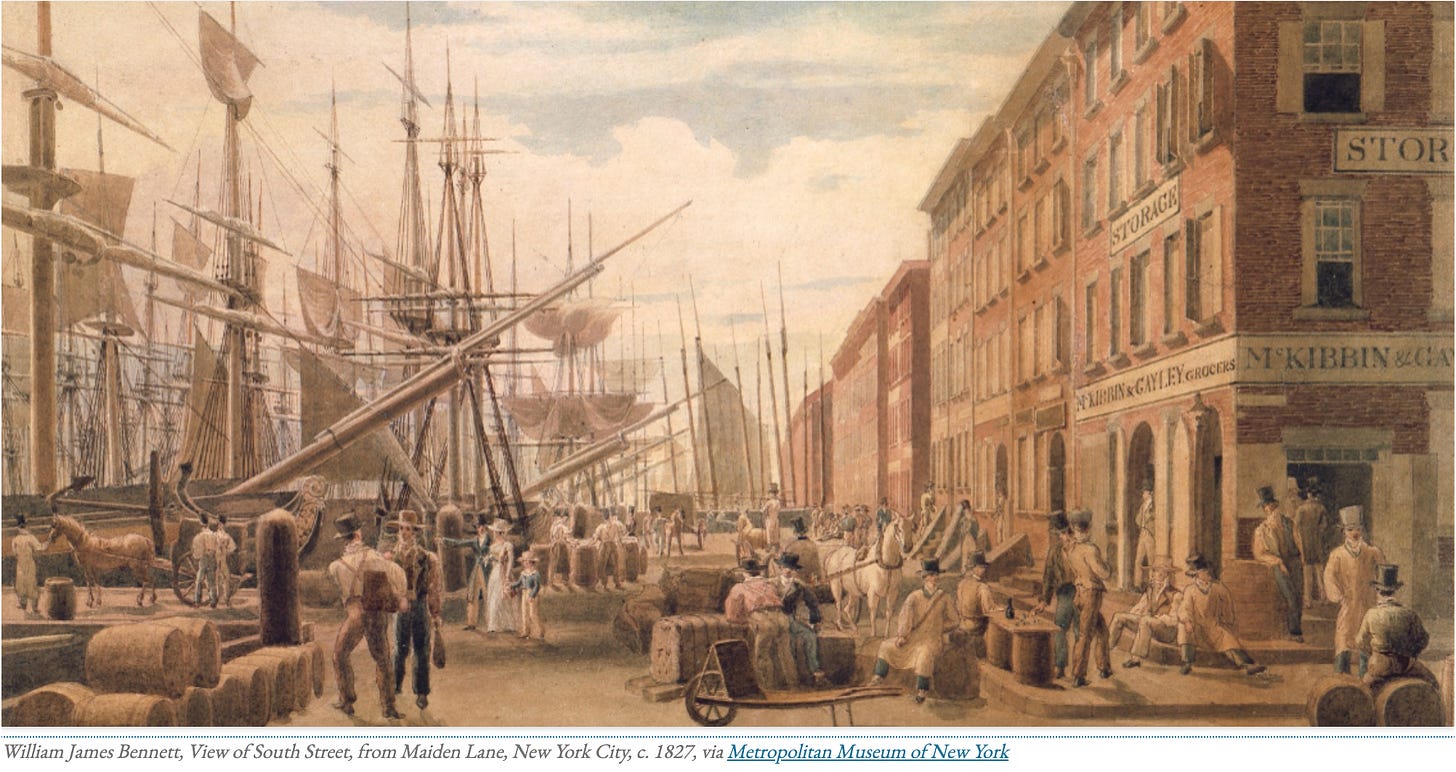

My working thesis is that America’s Founding Fathers and their immediate successors consciously designed and built a free society grounded in the inviolability of private property, the sanctity of contracts, and the freedom of commerce. In other words, the Founders created a laissez-faire constitution and government that would leave people alone to produce and trade. (See my essay on The Laissez-Faire Constitution for a fuller discussion of how the Founders created a laissez-faire government.) The result was the stunning and world transformative economic miracle that was the American economy in the nineteenth century.

Let us begin by defining our terms. Specifically, how did the eighteenth-century Anglo-Americans and their progeny understand what commerce is?

Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary of the English Language (1775) defined the word “commerce” as “Intercourse; exchange of one thing for another; interchange of any thing; trade; traffick.” Fifty-three years later, Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language defined commerce as “In a general sense, an interchange or mutual change of goods, wares, productions, or property of any kind, between nations or individuals, either by barter, or by purchase and sale; trade; traffick.”

Commerce means trade, but trade is built on the division of labor, creation, and production. There is no commerce or trade without things that have been made, or a service of labor (physical or mental) and time. The things produced could be agricultural or manufactured goods, and a service involves work of one kind of another for remuneration. For the purposes of this essay, I am expanding the definition of commerce to include production and work, and I am assuming the existence of a division of labor as a necessary condition of commerce.

The Moral Basis of Economic Freedom

The American Revolution was fought, in part, to escape the mercantilist taxes, duties, regulations, and trade barriers imposed on American merchants and consumers by the British Parliament in the twelve years after 1764 (e.g., the Sugar, Townshend, Tea, and the Boston Port Acts). In 1774, Thomas Jefferson noted in his Summary View of the Rights of British America that the American people claimed and possessed “the exercise of a free trade with all parts of the world, . . . as of natural right.” In other words, trade is natural, right, just and therefore good and necessary for human flourishing.

One of the obvious consequences of the American Revolution was the freeing of both internal and external trade and the creation of new markets around the world. Just as the Revolution was coming to an end, Gouverneur Morris exclaimed that the American people were “the first-born children of the commercial age.” What would come to be called laissez-faire capitalism, which is the result of a laissez-faire constitution and government, began in America.

With the end of the War of Independence, the American people were no longer bound legally or politically to the demands of British mercantilism, which meant they could now trade with whomever they wanted—and trade they did. In a 1779 essay (republished in 1794), Pelatiah Webster, one of America’s rising political economists, wrote in an essay dedicated to the Continental Congress, that “FREEDOM of trade, or unrestrained liberty of the subject to hold or dispose of his property as he pleases, is absolutely necessary to the prosperity of every community, and to the happiness of all individuals who compose it.” To that end, Webster proposed to the Congress that it remove “every restraint and limitation from our commerce.” Trade, he advised, should “be as free as air” and thus every man can “make the most of his goods in his own way and then he will be satisfied.”

The Founding generation understood that beneath the political and economic conditions necessary for the free flow of commerce lay deeper moral causes. The ethical heart and soul of late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century American commerce—its inner dynamo—was the ethic of self-interest (rightly understood), which posited the revolutionary idea that individuals have a moral right to advance their lives via the pursuit of improved living conditions and wealth. Institutionalizing and deinstitutionalizing their natural right to the pursuit of happiness was, at the deepest philosophic level, the Founders’ greatest and most revolutionary task.

The implication of this ethic was that individual men and women had the right and the capacity to be both self-governing and self-reliant. Implied in this principle was the assumption that men and women could enter various relationships with one another on the mutually understood basis of self-interest and equality, which meant that all the traditional ties holding society together (e.g., rank, deference, personal dependencies, patronage, kinship, sentiment, etc.) were now cast asunder.

The Framers of America’s constitutional order intended to create a free-market society based on six political-economic principles, or what we might call the six elements of economic freedom: first, the freedom to think and invent; second, the freedom to work; third, the freedom to produce; fourth, the freedom to compete; fifth, the freedom to invest; and sixth, the freedom to trade. Quoting Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Pennsylvania’s George Logan noted in his Five Letters, Addressed to the Yeomanry of the United States (1792) that America’s prosperity was due to the “liberty” of its citizens “to manage their own affairs, their own way.” In other words, the freedom to be left alone to produce and trade was the defining characteristic of American life in the post-Founding world.

This new moral-economic doctrine assumed and promoted the idea that the pursuit of profit and wealth encouraged men to use their rational faculties in new and improved ways. Rather than simply obeying the commands of others, the new capitalist order liberated all men to think for themselves and to think rationally as they pursued different opportunities for improving their lives. By this system of reality-based thought, men could reconcile their self-interest with the demands of virtue, which had been seen traditionally as antipodes. By the natural system of economic freedom there was no necessary conflict between self-interest and virtue (e.g., particularly the virtues of rationality, independence, honesty, frugality, industriousness, courage, etc.). The moral laws of nature, Thomas Jefferson told the famous French economist, J.B. Say, “create our duties and interests,” such that “when they seem to be at variance, we ought to suspect some fallacy in our reasoning.” In other words, moral responsibilities and self-interest were seen to be not in conflict as they had for two thousand years, but as working together to enjoin harmoniously prescribed human relations.

Alexis de Tocqueville captured the moral meaning of this new American commercial spirit in Democracy in America, when he observed that the “Americans put a sort of heroism into their manner of doing of commerce.” The American man of production and trade, the Frenchman continued, “not only follows a calculation, he obeys, above all, his nature,” and that nature recognizes no limits to what to what it can achieve. “Nowhere,” says Tocqueville, does the American “perceive any boundary that nature can have set to the efforts of man; in his eyes, what is not is what has not yet been attempted.” The prototypical American was therefore “a man ardent in his desires, enterprising, adventurous—above all an innovator.” The Americans love commerce not so much for the financial gain they receive, Tocqueville surmised, but rather because “they love all undertakings in which chance plays a role” and because they love “the emotions that it gives them.” The new American spirit encouraged adventure and risk-taking.

Following Adam Smith and the French physiocrats, America’s revolutionary and post-revolutionary generation believed that exchanges between two or more parties would benefit all concerned so long as the trade was strictly voluntary. They believed that collaboration, cooperation, and exchange were best achieved when self-interested individuals were left free from external force and coercion, which meant in an environment of freedom. The political policy of laissez-faire leaves men and women alone to follow a reality-based ethic and the self-regulating mechanism and information conveyor that is the price system, which enables people to go in and out of win-win, cooperative relationships that are constantly evolving without the commands and violence of the State.

The Founders knew that prices serve as an economic barometer or as a signal for buyers and sellers that assists them in coordinating their individually self-interested behavior with that of tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of other people. They also knew that from the self-seeking actions of innumerable individuals, a natural economic-social order would emerge as the unintended consequence of their various activities. As Adam Smith put it so eloquently, an individual who “intends only his own gain” is nevertheless “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

In the years after 1776, American Revolutionaries designed and constructed state constitutions and governments that institutionalized a commercial republic. From there, they went on to create a national market system via the new federal Constitution and its government offspring that allowed individuals the freedom to pursue their own economic objectives while simultaneously encouraging networks of cooperation and collaboration among producers, competitors, traders, and consumers. The Americans were fast becoming the world leaders in free trade.

How did America’s Founding Fathers understand commerce, and what did they do to free it from political meddling?

The Laissez-Faire Constitution and Commerce

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was called in large measure to help unshackle American business and to liberate American commerce from various trade barriers imposed by state legislatures on the free flow of interstate trade. Furthermore, because state legislatures controlled their own trade under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress was unable to negotiate free trade agreements with foreign nations. Thus, the Constitution’s Framers gave to the new Congress in Article I, section 8 a grant of power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with Indian tribes.”

The key words to interpret in Article I, section 8 are the noun “commerce” and the verb “to regulate.” As understood and used by the delegates to the Constitutional Convention, commerce meant trade, exchange, and the transportation of goods. By “to regulate,” the founders did not define or use the word in the way in which we do today, which is to control or restrict trade; instead, by “to regulate,” the Founding generation meant something close to the opposite of what we mean today: it to free up trade or to make it regular or regularly free across the nation. This meant that Congress had the power to prevent the states from obstructing commerce. For instance, the Constitution prohibits the states from taxing imports or exports without the consent of Congress, unless said taxes are to cover the costs of inspection. The Constitution also imposes on Congress a prohibition on taxing “Articles exported from any State (Article I, Section 9).”

America’s laissez-faire Constitution of 1787 created large spheres of freedom for ordinary people to be left alone to pursue their self-interest, to produce and trade, compete, save, exchange money, and pursue happiness. The Constitution’s Framers created a political system that liberated hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans to work harder and get ahead in life. Over the course of the next century, intellectuals, politicians, Supreme Court justices, and certainly common Americans supported and carried out the Framers’ intent.

This interpretation of the Constitution’s commerce clause was later sanctioned by the Supreme Court. In 1824, Chief Justice John Marshall argued in Gibbons v. Ogden that the power to regulate meant “to prescribe the rule by which commerce is to be governed”—and the guiding “rule” was freedom. And in his concurring opinion, Associate Justice William Johnson wrote, “If there was any one object riding over every other in the adoption of the Constitution, it was to keep the commercial intercourse among the States free from all invidious and partial restraints.” Commerce must be free.

In sum, according to the original meaning of the Commerce Clause (at least as it relates to trade between the states), the goal of the Constitution’s Framers was to create a common market or a free-trade zone between the states. To that end, the Constitution empowers Congress to pass uniform bankruptcy laws, establish standard weights and measures, and coin and regulate the value of money.

Ninety-nine years after the Constitution was drafted, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Freeman Miller summed up perfectly the Framers’ understanding of commerce and the commerce clause in the Wabash Railway case of 1886:

It cannot be too strongly insisted upon that the right of continuous transportation, from one end of the country to the other, is essential in modern times to that freedom of commerce, from the restraints which the states might choose to impose upon it, that the commerce clause was intended to secure. . . . And it would be a very feeble and almost useless provision, but poorly adapted to secure the entire freedom of commerce among the states which was deemed essential to a more perfect union by the framers of the Constitution, if, at every stage of the transportation of goods and chattels through the country, the state within whose limits a part of this transportation must be done could impose regulations concerning the price, compensation, or taxation, or any other restrictive regulation interfering with and seriously embarrassing this commerce.

Miller confirmed the clear intention of the Constitution’s Framers to interpret the commerce clause as encouraging the free exchange of goods and services without government interference. He sought to free men from the shackles and coercion of meddling and grasping politicians. The commerce liberated by America’s laissez-faire Constitution was not a cause as much as it was a consequence and recognition of more fundamental moral principles—the right to the protection of private property and the sanctity of contracts.

Freedom and the Rise of Commerce

Post-Founding Americans embraced commerce and a free-market economy like no other people in history. In 1795, Phineas Hedges exuberantly sang the praises of commerce: “In a free government, commerce expands her sails; Prompted by a spirit of enterprize and a desire of gain, men venture the dangers of a boisterous ocean in pursuit of new commodities. With wider acquaintance of man the elements of the monk and the barbarian dissolve into the sympathizing heart of a citizen of civilized life.” Likewise, Republican congressman Edward Livingston toasted America’s rising glory this way: “The Colossus of American Freedom,” he exclaimed, “may it bestride the commerce of the world.” Commercial expansion in America’s nineteenth-century liberal society was rapid and mostly unregulated as America’s new-model man embraced hard work, competition, and the spirit of enterprise.

Jeffersonian republicans came to view commerce as more than just the economic transactions of businessmen via money in the pursuit of profits. In 1811, Jefferson translated and had published in America A Commentary and Review of Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws by the French Idéologue, Comte Destutt de Tracy. Tracy and his American students took a latitudinarian view of commerce as consisting of all forms of exchange. All exchanges, wrote Tracy via Jefferson, “are acts of commerce, and the whole of human life is occupied by a series of exchanges and reciprocal services.” In other words, commerce is what brings discrete individuals together in a harmonious relationship of give and take. The exchange of both material and spiritual values is, according to Tracy, “not only the foundation and basis of society, but . . . it is in effect the fabric itself; for society is nothing more than a continual exchange of mutual succours, which occasion the concurrence of the powers of all for the more effectual gratification of the wants of each.” Jefferson’s translation of Destutt de Tracy was one way for the former president to explain his political philosophy to his fellow Americans.

Not all Americans, though, were entirely supportive of what American society was becoming. In an 1800 address celebrating the 23rd anniversary of American independence (a curious dating of independence!), Columbia College Professor Samuel Mitchill, warned his fellow citizens about the “lust after property” that leads to men acquiring and developing an “incalculable number of artificial or acquired wants” that in turn become the “ruling passion of the mind” and expressed as a “most sordid avarice.” Mitchill also lamented the fact that “the voice of the people and their government is loud and unanimous for commerce.” The “inclinations and habits” of the American people seemed, according to Mitchill, “adapted to trade and traffic.” In fact, “From one end of the country to the other, the universal roar is,” the Columbia Professor scoffed, “Commerce! Commerce! at all events, Commerce!” Mitchill’s classical republican criticism of wealth and commerce was genuine but outdated. Going forward, very few Americans would share his concern. In fact, his reservations about America’s burgeoning capitalist economy only demonstrates its reality and power.

Mitchill’s moral assessment of commercial America was a decidedly minority viewpoint. In 1806, Samuel Blodget, one of America’s first professional economists, noted in his treatise, Economica, that immigrants to the United States “since our independence” seem to have come to America to live under “the best social system that ever was formed,” namely, the system of free or laissez-passer commerce, which “is the most sublime gift of heaven, where with to harmonize and enlarge society.” Blodget found commerce to be not only “a principal stimulus to all industry,” but it was also “the only deity who frankly tells its votaries, ‘by untouched credit and industry alone shall ye rise on my wings, to the temple of fortune and to fame.” It was during these early years that the uniquely American ethic of self-reliance and self-enrichment was born.

In April 1808, during the congressional debates over whether the United States should or should not suspend the Embargo Act, Josiah Quincy, one of America’s last remaining Federalists, offered his reasons for opposing the Embargo of the federal government, which, he said, was “cruel to individuals and mischievous to society.” He went on to defend the importance and benefits of free, unobstructed commerce and to identify its inner motor: “The best guarantees of the interest society has in the wealth of the members who compose it, are the industry, intelligence, and enterprise of the individual proprietors, strengthened as they always are by knowledge of business, and quickened by that which gives the keenest edge to human ingenuity—self interest.” America’s economic revolution was grounded on a political revolution that was in turn grounded on a moral revolution.

Four years after Quincy’s speech, even Samuel Mitchill, the dyspeptic professor now a congressman from New York and seemingly more reconciled to the mores and ambitions of his constituents, told his fellow members of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1812 that his Long Island constituents were “bred to commerce” and that the “spirit of business warms them.” Responding directly to Mitchill’s speech, Kentucky’s Henry Clay told his colleagues that the desire to engage in commerce “is a passion as unconquerable as any with which nature has endowed us.” Clay also noted that his colleagues “may attempt to regulate” commerce (i.e., in the coercive sense), but they certainly could not “destroy it.” The American people were all in for America’s burgeoning market economy.

Commerce, grounded as it is in self-interested motives and behaviors, was nonetheless viewed as a service industry by Jacksonian Americans. According to Gilbert Vale, “[c]ommerce is in fact an extension of the principle of the division of labor, and the profits which it affords is the remuneration for the labor of transporting the objects of commerce to the consumers.” As if by some sort of invisible hand, self-interested individuals maximizing their profits had the unintended but welcome consequence of elevating the wealth of the entire society. According to Nathaniel Niles, when men “enjoy liberty and are sure of its continuance, we feel that our persons and properties are safely guarded and this excites to industry which tends to a competency of wealth.” Likewise, George Logan argued that “The Yeomanry of America only desire what they have a right to demand—a free unrestricted sale for the produce of their own industry and not to have the sacred rights of mankind violated in their persons by arbitrary laws, prohibiting them from deriving all the advantages they can from every part of the produce of their farms.” Nineteenth-century Americans created the world’s first laissez-faire society.

Commerce and the Natural Society

But what would hold this individualistic, self-interested, self-seeking, self-reliant society together? What would prevent it from descending into social chaos?

The Founding generation and their children and grandchildren understood that it was meddling and grasping politicians who upset the natural order and harmony of a free society. It was power-lusting politicians acting in the name of the “common good” rather than self-interested producers and consumers who divided Americans one from the other. In 1827, Chief Justice John Marshall reminded his fellow Americans in Ogden v. Saunders that one of the central objects of America’s constitutional union was “to make us, in a great measure, one people as to commercial objects.” Marshall understood that commerce unites rather than divides. He knew that commerce and all that goes with it, rather than dividing or alienating people, brings them together in temporary and mutually advantageous relationships.

America’s new republican society would be held together not by Christian guilt or government coercion but by the bonds of free-flowing commerce, which in turn was grounded in self-interest, the inviolability of property, the sanctity of contracts, the division of labor, supply and demand, the price system, competition, and profits. Every day (in the context of the late eighteenth- and early-nineteenth centuries), tens or hundreds of thousands of business transactions consisting of buying and selling, trading or bartering, brought people together voluntarily in a natural harmony of mutual and even competing interests. Ironically, self-interested actions brought people together and motivated them to be decent if not benevolent toward one another.

Following Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, the Founders’ and early nineteenth-century American intellectuals and businessmen came to see that a competitive, profit-seeking system of market transactions resulted not in social atomism, social division, and social chaos, but in the truly natural system of human relations that mirrored the operating system of the physical universe. By liberating man’s self-interest within a system of rights-protecting justice, natural forms of association were built from the bottom up and with the added benefit of liberating human energy and producing unheard of amounts of wealth distributed far and wide. In America’s free-market society, independent, self-interested, profit-seeking, competitive individuals gained from the existence of other people who simultaneously participate with them in the division of labor and the unity of association. As Old-World constraints and regulations fell in the New World, Americans came to view the economy as a harmonic natural system with its own laws of nature regulating production and trade.

The antebellum American economy provided concrete evidence of how Smith’s “invisible hand” worked in practice. The whole system was largely undirected and mostly free from grasping politicians, and yet it worked harmoniously in predictable patterns. Discovering that the ordering mechanism of this harmonious system was located in the inner drive of men and women to improve their lives (i.e., in the pursuit of their self-interest) was nothing less than a revolution in moral and political thinking.

Even more remarkably, the Founding generation and their successors viewed competition, which is the epitome of self-interested action, as improving the condition of society as whole. Competition is both a natural and an automatic process that lowers prices, improves quality, and motivates discovery and innovation. In a special message to the United States Senate and House of Representatives in 1802, President Jefferson described economic competition as a natural process that “brings everything to its proper level of price and quality.” We might also add that competition helps to improve man’s moral condition by challenging men every day to improve their thinking and to work harder.

Day after day in America’s burgeoning, post-revolutionary market economy, hundreds of thousands of self-interested individuals in the pursuit of gain or profit determined the value of their trades based on supply and demand, the aggregate of which determined the overall prices throughout a nationwide market. According to Pelatiah Webster, one of America’s strongest proponents of a free-market society, the attempt by government meddlers to fix prices (including wages) constituted a violation of the economic laws of nature. Such attempts were built on the false conceit that market prices can be manipulated without deleterious, unintended consequences. Webster insisted, “the price that any article of trade will bring in a free, open market, is the only measure of the value of that article.” But if market prices are “warped from the truth, by any artifices of the merchant, or force of power, it cannot hold.” Such an “error, he continued, “will soon discover itself, and the correction of it will be compelled by the irresistible force of natural principles.” This self-correcting mechanism is built into the price system through the law of supply and demand. As a result, merchants could not raise prices too high nor can command-and-control political rulers “keep them too low.”

America’s best Founding-era political economists understood that the price mechanism, if left unobstructed, would result in increased production, improved quality of goods and services, an equilibrium of supply and demand, and maximized efficiencies. In other words, salutary economic outcomes were much more likely to be achieved if the market were driven by profit-seeking, individuals motivated by self-interest rather than controlled by power-seeking government bureaucrats acting in the name of the “common good.”

Pelatiah Webster understood that any violation of the natural system of liberty and property will, by its “most natural operation, produce effects very unsalutary, if not fatal.” By contrast, if trade can be “let alone,” it will “make its own way best, and, like an irresistible river, will ever run safest, do least mischief and most good, when suffered to run without obstruction in its own natural channel.”

James Madison held a similar view about the natural system of economic liberty. In a speech to the first meeting of the U. S. Congress in 1789, Madison declared himself a “friend to a very free system of commerce, and hold it as a truth, that commercial shackles are generally unjust, oppressive, and impolitic.” He also thought it to be a basic economic truth “that if industry and labor are left to take their own course, they will generally be directed to those objects which are the most productive, and this in a more certain and direct manner than the wisdom of the most enlightened Legislature could point out.” The Father of America’s laissez-faire Constitution was a proponent of what would soon come to be called laissez-faire capitalism.

At the macro level, the result of a system of economic freedom was a patterned, lawlike regularity that connected innumerable men and women in a market system that the Scottish historian and moral philosopher, Adam Ferguson, described in his An Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767) as “the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.” Out of the seeming chaos of freedom and countless market transactions came a new kind of social order that held society together without the strong arm of government dictating how men should behave.

Conclusion

Without question, the most subversive element of this new view of human relations that came out of the American Revolution was the suggestion that government supervision of the economy was not only counter-productive but immoral—immoral because it assumed, falsely, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, that the mass of mankind were born with saddles on their backs waiting for those naturally booted and spurred to ride them by the grace of God—immoral because the claims of some to use coercive force against peaceful citizens was based on the illegitimate concept of the “common good,” a common good known mysteriously to only a few who shared their secret knowledge with their fellow rulers. As Jefferson put it: “the rights of the whole can be no more than the sum of the rights of individuals.”

The idea of laissez-faire constitutionalism gave the lie to two thousand years of political imagining and conceit that a self-appointed ruling elite of philosopher-bureaucrats could manage something as complex as a market-based economy.

The new free-enterprise system envisioned by John Locke, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and nineteenth-century Americans was morally superior to the traditional view of society, which assumed that ruling, henpecking, telling other people how to live was man’s noblest activity and that a ruling elite had a natural moral right to rule when they clearly did not. It turned out that men could rule themselves quite well if left alone.

Ironically, the unintended consequence of everyone pursuing their own self-interest was a system of social benevolence and harmony, legal symmetry, commercial order, and community cohesion. America’s laissez-faire society gave a new meaning to e pluribus unum.

Whoever would have thought?

**A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.