My apologies for missing the last two weeks of posts. I’ve been simply overwhelmed with work at my day job, and I’ve also been writing in a white heat to finish what will be a multi-part series of essays on the story of American freedom and the promise of American life. I’ve also been caught up the news events of the last couple of weeks.

Today’s post represents a few of my thoughts on what’s happening in higher education and at Harvard in particular. This is my Harvard story presented as two stories in one.

“Niebuhr was right,” said Goethe, “when he saw a barbarous age coming. It is already here, we are in it, for in what does barbarism consist, if not in the failure to appreciate what is excellent.”--Johann Peter Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe, March 22, 1831.

STORY ONE—Harvard 1990-ish

Harvard University was a place that once meant a great deal to me. While never a formal, tuition-paying student there, I did spend two years at Harvard as a “pre-doc” in the Constitutional Studies Program. During those two years, I wrote my dissertation in the bowels of Widener library, audited two classes (and wrote the essays for one of them), went to seminars and lectures, participated in the meetings of an underground, samizdat drinking club of dissident “intellectuals” (we called ourselves, predictably enough, the “Saving Remnant”), practically lived in the Harvard Bookstore, ate the best hamburgers in the world at Mr. Bartley’s restaurant, saw Camille Paglia give the most entertaining public lecture that I’ve ever witnessed, and spent meaningful time getting to know half a dozen or so Harvard faculty members.

You might say I was sort of an intellectual vagabond like the wandering vagantes of the Middle Ages, who traipsed around Europe looking for wise men (and women) with whom to study. During that time and clearly lacking any sense of social or intellectual inhibition, I went in search of those from whom I might learn something.

I became friendly during those two years and met frequently with some of Harvard’s most esteemed faculty members, such as Oscar Handlin, Donald Fleming, and Stephan Thernstrom from the History Department and Judith Shklar from the Government Department. I was always struck by how generous they were with their time. I was, after all, a nobody from their perspective, and yet they took the time to speak with me for hours on end. I was just some young intellectual hobo who apparently asked moderately interesting questions. Initially, I schlepped up to their offices in Widener Library, introduced myself, asked if they had a few minutes to talk (which they always did), and off we went. I spent innumerable hours with these great scholars, and I learned much from them. I soaked up their brilliance and wisdom. All of them were at the end of their careers, and now, in hindsight, I wonder if they tolerated me because they realized that Harvard was becoming a shell of its former greatness—that it had become overtly politicized and full of poseur students who were not particularly serious about anything other than social climbing and career advancement. I think they just wanted someone with whom they could have a serious conversation.

I should pause here and fill in some of the backstory explaining how I got to Harvard in the first place.

At the time, I was a Ph.D. student at Brown University just down the road in Providence, Rhode Island, working under the supervision of the greatest-living historian of the American Revolution, Gordon S. Wood. After I had taken his remarkable classes, extracted from him his extraordinary knowledge of the revolutionary-found period, served as his teaching assistant, and passed General Exams, Professor Wood kindly took me out for lunch at the Brown Faculty Club, where he said to me, “Thompson, you should move to Boston, write your dissertation, and send it to me when it’s done,” which is precisely what he said and precisely what I did. Unlike with many of his other graduate students, there would be no hand holding, no advice, no mollycoddling, no editing, no nothing on the dissertation. For many a graduate student this would be the equivalent of a banishment, but for me it was a godsend. I’d like to believe that Professor Wood had enough confidence in me to cut me loose and let me forge my own way. This was the single most important moment in my early academic career. My time in the wilderness helped me to develop the independence of mind and work ethic that is necessary for anyone who wants to live a life in the pursuit of truth and wisdom. I think Professor Wood knew that, and I think he trusted me enough to let me go—or push me out! Either way, Professor Wood did that for me, and I will always be thankful to him for the blessing.

And so, I moved to Boston and set out to write a dissertation on the political thought of John Adams. Fortunately, at the same time, I was also offered a “pre-doc” with the Constitutional Studies Program at Harvard run by Professor Harvey C. Mansfield from the Government Department, which gave me access to Widener Library, where I worked from morning to night. (Two years later, I sent Professor Wood a 600+ page dissertation. He approved it with no edits or rewrites.)

More important to me than my delightful conversations with various Harvard faculty were two classes that I took as an auditor. These classes were with two of Harvard’s legendary scholars, Harvey C. Mansfield and Bernard Bailyn.

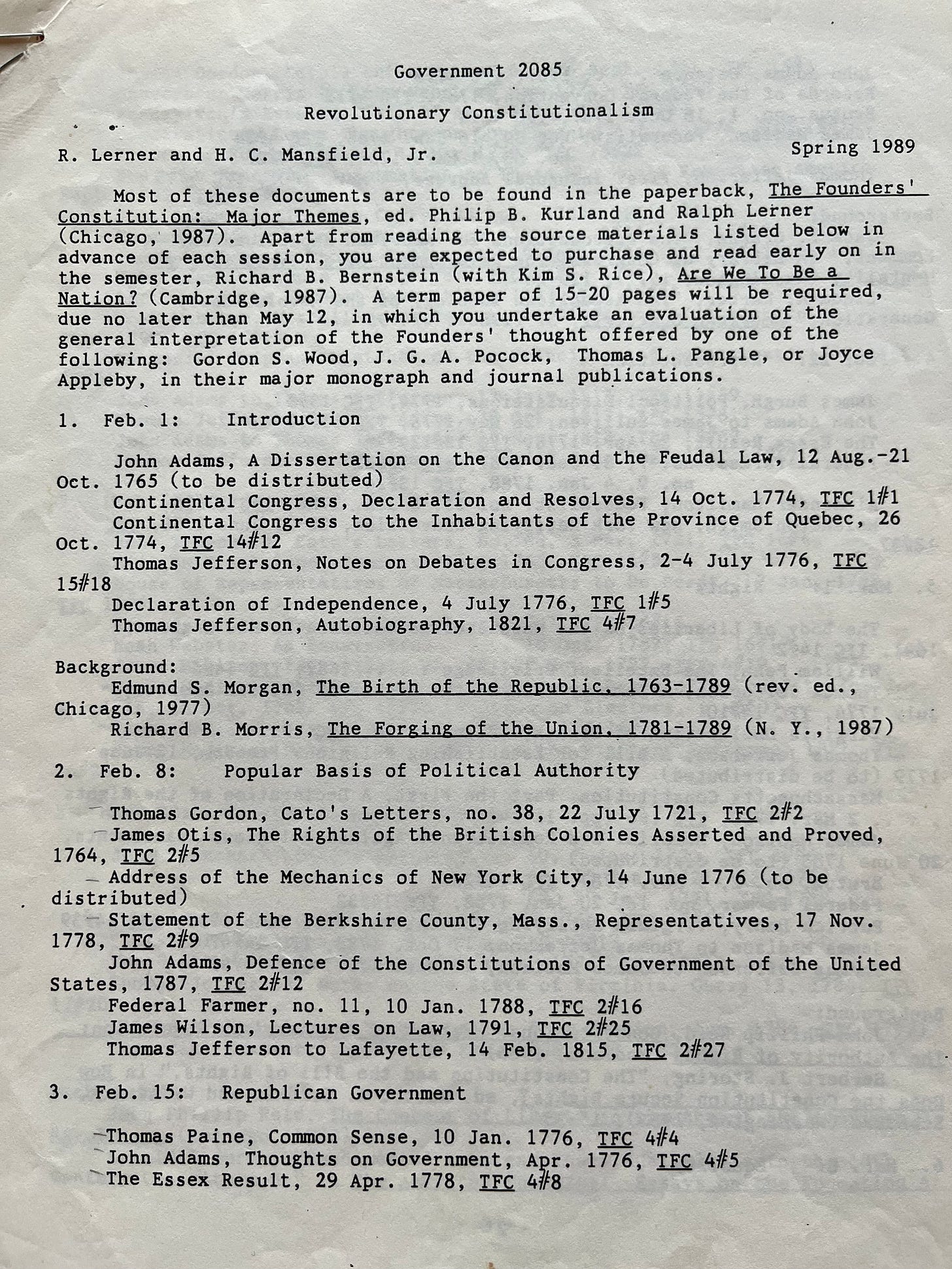

In the Spring of 1989, I attended a seminar in the Government Department team-taught by professors Harvey C. Mansfield and Ralph Lerner (visiting from the University of Chicago). The course was titled “Revolutionary Constitutionalism.” Lerner and Mansfield (two of America’s best political theorists) were, not surprisingly if you know them, brilliant, provocative, and challenging. Because it was a seminar, the burden was on the students to have something interesting to say every class. I prepared for each one of the classes like I had never prepared before. I was determined to show professors’ Lerner and Mansfield that I had the right stuff. Though only auditing the course, I wrote the papers, which professors Lerner and Mansfield graciously read and graded. (And no, I did not receive the infamous “C-” from the man affectionately known around Harvard Yard as “Harvey C- Mansfield.”)

I can also mark this class as representing an intellectual turning point in my life. It was the moment when I transitioned from being an intellectual dilettante to experiencing for the first time what it means to live the life of the mind. I remember as though it were yesterday the day I wandered through Cambridge for a couple of hours and living entirely inside of my head, completely unaware of my surroundings. In previously unexplored regions of my mind, I discovered new places that I barely knew existed. It was as though I were outside of time and space. I literally lost all sense of where I was walking that day as well as the transition from day to night. When I returned to terra firma, I then spent a good two hours trying to find my way home! I am also eternally grateful to Professors Lerner and Mansfield for their continuing support and counsel over the years. Mr. Lerner was the “outside” reader on my dissertation, and Mr. Mansfield has been a supporter of my career for over three decades.

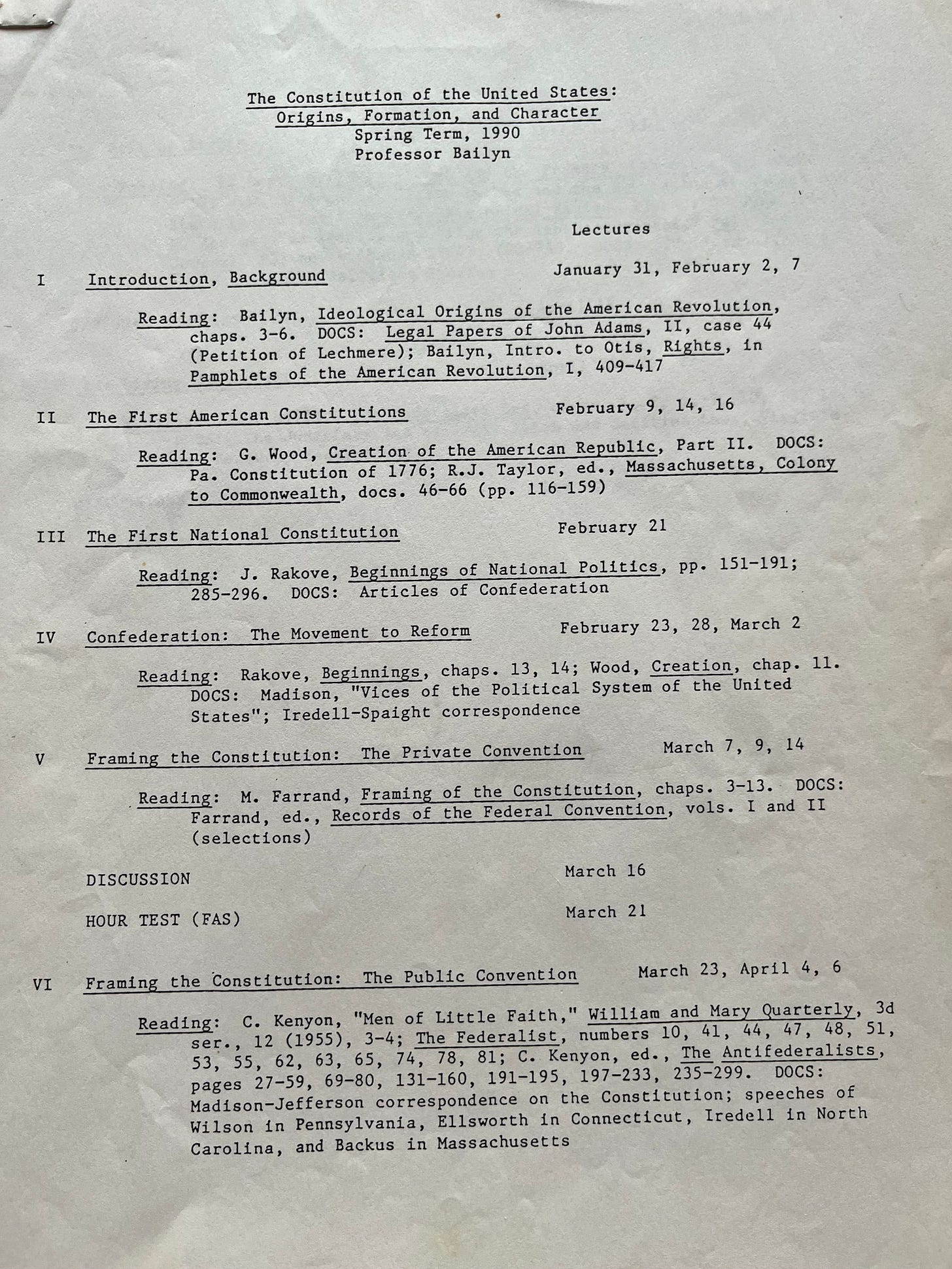

A year later, in the Spring term of 1990, I attended what I believe was Professor Bernard Bailyn’s last lecture course at Harvard. Mr. Bailyn, for those of you who have never heard of him, was probably the greatest twentieth-century historian of colonial America. He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History, a popular lecturer at Harvard, and a legendary dissertation advisor. Professor Bailyn’s (final?) course was titled, “The Constitution of the United States: Origins, Formation, and Character” and it was held in the Law School’s famous Langdell Hall. Befitting the great man’s “Last Lecture” course, the auditorium was packed for the entire semester. It was literally standing room only. The room was full of undergraduates, graduate and law school students, and a few faculty members. The class, which met on Wednesdays and Fridays, was an event. The moment that Professor Bailyn entered the hall from a side door, the room went automatically silent. Not a peep was to be heard. The great man would then mount the elevated lectern and deliver with seriousness, dry wit, and immense erudition lectures as graceful and penetrating as any I’d ever heard. Mentally, I was totally focused and locked in.

After Professor Bailyn’s first lecture, I made my way down to the pit at the front of the room and asked him a question or two. At a certain point, he interrupted me and asked with some incredulity, “who are you?” I told him that I was a student of Gordon Wood at Brown, and that I hoped he wouldn’t mind my sitting in on his class. (Wood was Bailyn’s best and most accomplished graduate student, which made me Bailyn’s academic grandchild!) And thus began a beautiful relationship that semester. After almost every class meeting, Professor Bailyn and I would walk back to his office and he would invite me in for a chat. The conversations were always the same: we would talk history (which he loved to talk about) and political philosophy (which he didn’t like to talk about) for exactly twenty minutes at which point he would stand up as I was in the middle of saying something, which was his sign that I was to stop talking as the conversation was now over. During the one class of the semester that I missed due to sickness, Professor Bailyn, noticing my absence, wrote my name on the blackboard and asked the class if anyone knew where Mr. Thompson was and why I wasn’t in class. Within minutes after the end of class, I received a phone call from the woman who sat next to me in class telling me that Professor Bailyn wanted to see me asap. I went to his office the next day, and he seemed rather relieved to see that I was not abandoning our twice-weekly conversations.

Over the years, Professor Bailyn and I kept in touch a little bit. I last saw him in 2017—I think. He was around 95 at the time and was still working every day in his Widener Library office. I arrived without any advance warning hoping that he might still be working in his office. I knocked on the door and heard nothing. I knocked again and this time I heard a gruff voice say, “come in.” I tried to enter, but the door was locked. I knocked again shouting through the door that it was locked. Thirty seconds later, I heard feet slowly shuffling toward the entrance. He had no idea who was on the other side. The door then flung open in a way that indicated a sense of irritation—irritation because he was clearly in work mode and deep in thought. (He was working on another book, and had a pencil propped up by his ear lobe.) And there we stood looking at each other. I was smiling and he was grimacing. I said, bursting out, “Hello, Professor Bailyn, it’s me Brad Thompson. I took a class with you 27 years ago.” He then focused on my now much older face and said, “Ah, yes, Thompson. Nice to see you. Come in.” We hadn’t seen each other in well over two decades. We had a wonderful conversation that day about what he was working on, what I was working on, and unexplored areas of early American history. I told him about my soon-to-be-finished book, America’s Revolutionary Mind. He barked at me to hurry up and finish it because he very much wanted to read it. I promised him I would. And then, per usual, he stood up and I stopped talking as it had always been. He had to go back to work. Just like the old days. America’s Revolutionary Mind was eventually published in November 2019, and I sent Professor Bailyn a copy a few months later. I’m not sure he ever received it, though. By then, I’m told he had moved into a care facility, and he passed in August 2020. It was the end of an era.

Even though I was never formally a Harvard student, the place meant something to me. It represented the epitome of what a serious university should be as summed up in its motto: “Veritas”! I no doubt had an overly romantic view of the place, but in my naïve mind it stood for the best of higher education. My time there was special. This is the Harvard I love.

Sadly, if not tragically, that Harvard is gone. It no longer exists.

STORY TWO—Harvard 2023

Fast forward to today.

Harvard University has been in the news this last week for all the wrong reasons. As I’m sure you all know by now the three stooges of higher education, Harvard President Claudine Gay along with Presidents Liz Magill of the University of Pennsylvania and Sally Kornbluth of MIT, caused a storm of controversy with their appearance and testimony at a congressional hearing in which they were grilled and drilled by congresswoman Elise Stefanik (R-NY).

I think it’s fair to say that many Americans were disgusted by the smug, self-satisfied, condescending testimony of this troika of mediocrities who run three of America’s best-known (as opposed to best) universities.

The question asked of all three university presidents by Stefanik was simple: At your university, does the calling for the genocide of Jews violate your university’s code of conduct or rules regarding bullying or harassment, yes or no? (Imagine, by contrast, if the question had been: “At your university, does the calling for the genocide of Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, or Team LGBTQ+ violate your university’s code of conduct or rules regarding bullying or harassment, yes or no?” I’m pretty sure in each instance the answer would have been an immediate, unhesitating, and very loud, “YES.”)

The answers of all three presidents to Stefanik’s question were virtually the same (as though they were all reading from a prepared seminar book): the calling for the genocide of Jews could be a violation of university policy only if it led to actions taken against Jewish students. In other words, it would only be a violation of school conduct after the genocide! Magill and Gay also repeatedly said that statements calling for the genocide of Jew were “context dependent.” The suggestion being that the current campus demonstrations calling for “intifada from the river to the sea—Palestine will be free” are justified given the “context.” The so-called “context” being Israel’s ongoing at attempt to defend itself and to eliminate the butchers of Hamas. These dishonest and mealy-mouthed responses were eviscerated by Stefanik, and they have been roundly and deservedly condemned by the general public.

Maybe the deepest philosophic point to come out of the testimony was the revelation that Harvard’s now mordantly comical motto, “Veritas” (i.e., Truth) is a sick joke. In her testimony, President Claudine Gay spoke of “her truth” (i.e., her subjective truth ) and “context-dependent” truth (i.e., socially-subjective truth as determined by those in power) as opposed to The Truth. Gone now from the so-called “Ivy League” is the greatest discovery of Western Civilization, i.e, the idea that truth denotes a relationship between the human mind (reason and logic) and objective reality. In the “so-called ‘Ivy League’” (and yes, this is how we should all now refer to it), the concept truth is a toy or play thing to be manipulated and controlled rhetorically by those seeking power over others. The new truth is defined subjectively as a function of either individual whim or group identity. In other words, we live in a post-truth society.

You can see their disgraceful and embarrassing testimony here:

In the days since their congressional testimony, President Magill of Penn was forced to resign in abject disgrace. The pressure was then on Harvard to fire President Gay. As calls for Gay’s resignation or firing reached a fever pitch, journalists Christopher Rufo, Chris Brunet, and Aaron Sibarium published on X (formerly known Twitter) and then in various print publications overwhelming and damming evidence that Claudine Gay had plagiarized parts of her doctoral dissertation as well as several articles since then (see here, here, and here). The Harvard policy on plagiarism is clear, and Gay clearly violated it.

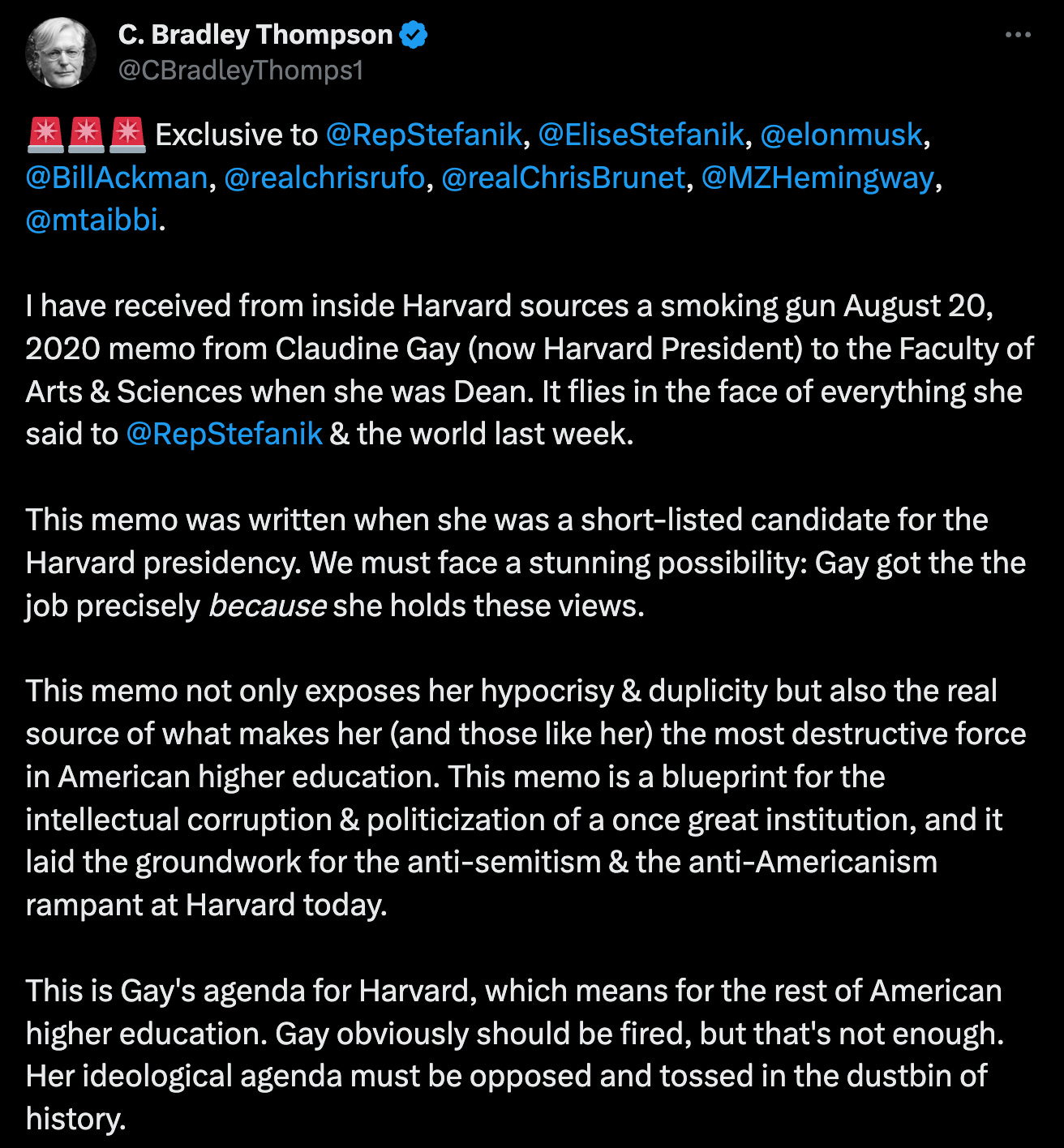

Then, on Saturday, December 9, I received an email (indirectly) from a faculty member at Harvard, which included as an attachment an August 2020 memo that then Dean Claudine Gay sent to the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. I then Tweeted Gay’s memo with an introduction. Here’s a screenshot of my Tweet (minus the Gay memo), which I’ll summarize below the screenshot.

Gay’s memo is an infantile and embarrassing word salad of woke and D-E-I gobbledygook. Consider her core assumptions:

People across the world have risen up in protest against police brutality and systemic racism, awake to the devastating legacies of slavery and white supremacy like never before. The calls for racial justice heard on our streets also echo on our campus, as we reckon with our individual and institutional shortcomings and with our Faculty’s shared responsibility to bring truth to bear on the pernicious effects of structural inequality.

According to Gay, it is the primary responsibility of Harvard and all institutions of higher learning to combat “systemic racism” and “structural inequality.” More directly: Gay is promoting “racial justice” as Harvard’s primary purpose and “anti-racist action” as its modus operandi. Harvard is to be revolutionized and transformed from an institution of higher learning into an indoctrination center, the purpose of which is to promote an extremist, far-left-wing ideological agenda. Ironically, such ideals and actions are apparently needed—and desperately needed—at of one of America’s most liberal universities. What this means, of course, is that all protests and riots (or, at least, the right ones)—including the ones that took place in the United States in the summer of 2020 when our cities burned from BLM/Antifa riots—are legitimate to combat the greater evil.

Gay’s memo (we can call it the Gay Agenda) is not only a blueprint but it’s also a call to action, the same kind of action that we’ve seen on college campuses since the October 7 genocide of Jews by Hamas (in the name of the Palestinian people). The memo set the institutional foundation and is an action plan for the recent protests at Harvard and other college campuses around the U.S. calling for the extermination of the Jewish people. The tropes and mentalité of the Gay Agenda should remind us all of Martin Heidegger’s “inner greatness” speech on the need to transform higher education in Nazi Germany.

In Gay’s mentally dysmorphic worldview, only power and those who wield exist. She therefore reminds her colleagues that “Change is messy work” and that it will make many “uncomfortable.” This is code language, of course, for the notion that eggs must be broken to make the new equity omelette. The Gay Agenda sanctions the identification, objectification, and brutalization of the “oppressor” class (i.e., non-leftists) by those at America’s so-called Ivy League institutions who speak for the “oppressed” class. The end shall justify the means. Violence against the oppressor class is understandable if not simply just.

Gay’s 2020 memo also flies in the face of everything she said to Representative Stefanik in the congressional hearing from the week before. In her congressional testimony, Gay projected little more than evasive and soft moral relativism. Her 2020 memo represents, by contrast, what she really thinks: it’s her call to action. This is a real-life example of what Rudi Dutschke meant by the “long march through the institutions.”

I have no space here to write about the obvious double-standards and fatuous hypocrisy of Gay’s memo and her testimony.

To repeat from my Tweet: it is important to note that Gay’s memo was written when she was a short-listed candidate for the Harvard presidency. Thus, we must face a stunning possibility: Gay got the job precisely because she holds these views.

This is Gay's agenda for Harvard and apparently the agenda of the Harvard Corporation and the Board of Overseers, which means this is the agenda for the rest of American higher education because everyone follows Harvard.

Remarkably, my Tweet blew up X. Within 48 hours the Tweet had received 18+ million views!

This was due, in part, to the fact that Elon Musk retweeted my post with this message:

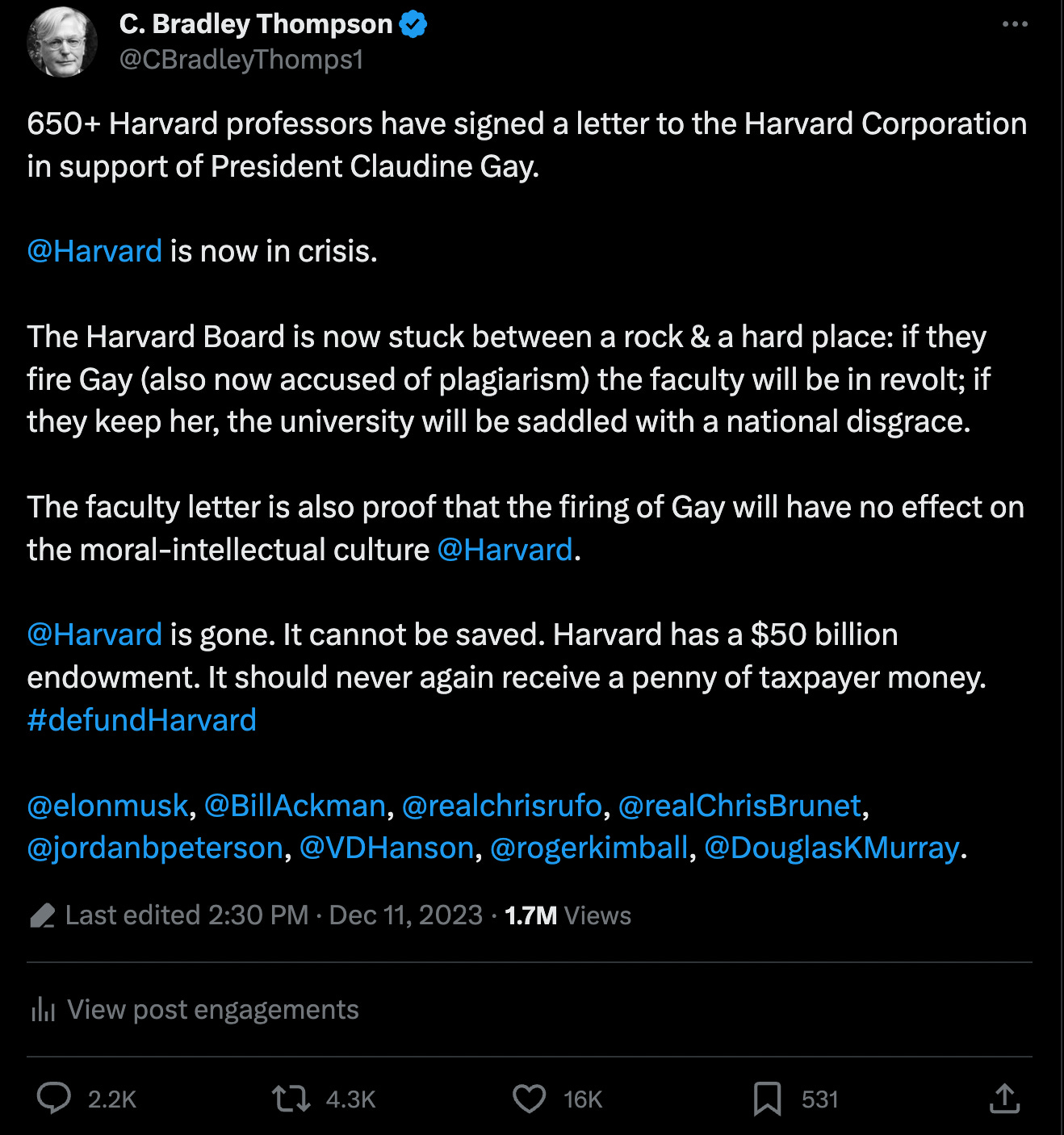

The day before my Tweet went viral, a large group of Harvard faculty, primarily in the humanities and social sciences, published a letter supporting Gay. Two days later, I posted my response to it on X:

Harvard’s version of a Board of Trustees then met to discuss Claudine Gay’s future at Harvard, which seemed all but over. The odds that Gay would be fired seemed like a sure bet. It was a virtual done deal.

Never in the history of American higher education were there such self-evident grounds to fire a college president. She had embarrassed Harvard with her testimony, and she had been publicly outed as a serial plagiarizer and a low-rent ideologue. No person in America could keep their job under these circumstances. Her ouster was a slam dunk, or so we thought.

Earlier this week, the Harvard Corporation announced that it will not fire Claudine Gay. This just might be the greatest scandal in American academic history. It’s a disgrace.

To paraphrase Marcello from Shakespeare’s Hamlet: There is something rotten at Harvard. The institution is obviously corrupt from top to bottom—the Corporation is corrupt, the administration is corrupt, the faculty is corrupt, and the student body is corrupt. Harvard has become a self-caricaturing clown show. It cannot be reformed; it cannot be saved; it’s gone.

The “Gay Affair” represents, figuratively speaking, the end of all that was good and great about Harvard.

Harvard is now the place of the living dead.

It is with the greatest sadness that I now say (figuratively), Harvard delenda est!

Social Justice is the phoenix that arose from the ashes of Marxism, which crashed catastrophically everywhere it was tried but was given a safe space to recover (and rebrand) in the Humanities departments of American academia. Out went yesterday's sacred protagonists of the Permanent Revolution, the proletariat—by the 60s at latest it was obvious to all the Left gurus that working people scoffed at them and would not exchange their countries, families and faith for the stale wafer called "Critical Consciousness"—so they were swapped out for the Wretched of the Earth who then became today's "marginalized".

I only raise this in the hope of providing some clarity to the discussion: Left morality is always based on Who/Whom and Left morality always states that it's okay to kill, cheat, steal, lie in front of Congress etc, as long as it's in service of "the Revolution".

Now that Social Justice is the official ideology of the global corporate state and the new state religion of the American elite, it's important for everyone to realize that our new leadership class doesn't believe in liberalism or its principles—but they will twist and mouth them if it helps them get their way in the moment.

Like all prior Left takeovers these people cannot be trusted, tamed, or dealt with in good faith. They will have to be removed somehow.

So, Brad. I never cease to be amazed by your revelations about your own journey in pursuit of Truth. I was 20 years ahead of you but took a different path, living a life in the trenches rather than of the mind, which I now sometimes regret. We have ended up in pretty much the same place. You are so much better at talking about it than I am, which is somewhat disappointing at an age when about all I can do is talk. A few years ago my undergraduate Alma Mater Vanderbilt University (BA Philosophy 1967) reached out with an invitation to attend the demolition of the Carmichael Tower, its first high rise dormitory, finished my senior year, which was to be replaced by some even grander undergraduate digs. I was among the first residents, which, I supposed, accounted for the invitation. Having attended to the deterioration of a once fine university with dismay through the years, I replied that I would be pleased to attend...provided the Chancellor were chained to a chair on the roof and I got to push the button. I never heard back and watched it live on local TV. Oddly satisfying nonetheless.