In 1793, the radical phase of the French Revolution was starting to expand and intensify. The Jacobins were now in power, and the resulting Terror was beginning to make itself felt on the people of France. The year witnessed mob rule, revolutionary riots, massacres, summary executions by guillotine, genocide in the Vendée, civil war, war, and the beheading of the King Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, followed by the execution of Queen Marie Antoinette nine months later. France was in a state of social and political chaos.

But what happens in France rarely stays in France. The ripple effects of the French revolution were felt in America, and, consequently, the United States was confronted with its first major diplomatic and foreign policy crisis. In fact, the French Revolution had a traumatic impact on American domestic politics as well. It radicalized one political party and made the other one more conservative.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, most Americans—even its most conservative citizens—viewed it as an extension of the American Revolution and were therefore favorably disposed to its ambitions. Four years later, however, America’s founding consensus began to rupture over events in France. The fracturing process began with the shocking events of August 10, 1792, when Louis XVI was deposed and incarcerated, and revolutionary forces assumed control of the government in France.

This was the moment when many Americans, particularly those of a Federalist persuasion, began to turn against the revolution in France. And by early 1793, when it was clear for those with eyes to see that the French Revolution had gone sideways, many Americans of a more conservative bent turned hard against the revolution. Looking back on that time, Fisher Ames from Massachusetts exclaimed, “Behold France, an open hell, still ringing with agonies and blasphemies, still smoking with sufferings and crimes, in which we see . . . perhaps our future state. There we see the wretchedness and degradation of a people, who once had the offer of liberty, but have trifled it away; and there we have seen crimes so monstrous, that, even after we know they have been perpetrated, they still seem incredible.” Ames’s view of the French Revolution echoed Edmund Burke’s description of events in Paris as a species of political vandalism that was little more than a “monstrous tragi-comic scene.”

Ames’s reaction to the French Revolution was not true for all Americans, though. Those of a Republican if not a radical persuasion were, by contrast, enthusiastic supporters of the revolution in France and much that went with it. Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a Republican from western Pennsylvania, declared that the “cause of France is the cause of man.” Thomas Jefferson, in a stunning letter to his former secretary William Short who was still in France and reporting to his old boss eye-witness accounts of the events in Paris, openly approved of the butchery associated with the Terror. Though he claimed to deplore the fate of the victims of the Terror (including the barbaric murders of a few people with whom he was acquainted), Jefferson rationalized their deaths as necessary for the success of the revolution:

My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it now is.

Both Ames and Jefferson shared portentous visions of a new world borne from the ashes of the French Revolution, the former viewing the revolution in apocalyptically negative terms and the latter in apocalyptically positive terms. France’s political crisis divided Americans and caused them to choose sides. The development of America’s two-party political system was, for instance, partly the consequence of the differing views held by Americans on the French Revolution.

The philosophic differences between Federalists and Anti-Federalists over the ratification of the Constitution in 1787 and 1788 were, for instance, differences of degree and not of kind, and they were differences of means and not of ends. By contrast, the competing views of Americans only a few years later over the merits and demerits of the French Revolution were differences of kind and differences over the purposes of government. In other words, the reception of the French Revolution in America caused a fundamental ideological and political rupture in the young republic that would never fully heal. The French Revolution even ended longstanding friendships in America. In old age, John Adams told his recently reunited friend, Thomas Jefferson, the “first time, that you and I differed in Opinion on any material Question; was your arrival from Europe; and that point was the French revolution.”

The status of the French Revolution in America came to a head in the six months between September 1792 and February 1793 when France proclaimed itself a republic, executed its king, declared war against Great Britain (along with its allies Spain and Holland), and appointed Citizen Edmond Genêt minister to the United States. These events caused the Americans’ revolutionary consensus to unravel.

On the surface, the ideological-political divide that opened in America was fought over questions of foreign policy and international relations. But just under the surface, the French Revolution and all that came with it was also affecting American domestic politics.

The specific issue that came to divide America concerned its two 1778 treaties with France. During some of the darkest days of the Americans’ war for independence against Great Britain, the infant nation signed a “Treaty of Alliance” and a “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” with France that were important factors in its eventual victory. Sentimentally, morally, and legally, the Americans owed a debt to France.

The two immediate political questions under discussion in 1793 related to the treaties were: 1) were the Gallo-American treaties of 1778 still in effect in 1793, and 2) if they were still actionable, how or in what way did they apply to the current situation?

What was most remarkable about the ensuing debate in America was that it quickly and automatically turned from a political-diplomatic debate into a moral-political-diplomatic debate about the moral nature and obligations of treaties. Specifically, the fundamental issue was reduced to this question: is the United States morally obliged to fulfill its treaty obligations with France?

Before we proceed, it is important to remember that America’s Founding Fathers created the world’s first philosophically inspired and grounded nation. More specifically, the United States of America was founded on certain moral-political principles that can be summed up as follows: the sole purpose of government is to protect the unalienable rights of individuals. In the light of this purpose, it was critically important, therefore, that the Founders first design and institutionalize a limited, constitutional government, and then secure the integrity of their system by pursuing domestic and diplomatic policies and programs that protected and advanced the moral principles on which the constitutional superstructure rested. Possibly the single most remarkable aspect of American politics in the nation’s founding years is the degree to which virtually every political and constitutional issue was reduced to its moral core.

This essay, then, is not primarily about treaties or contracts. At the deepest level, it’s about the Founders’ moral vision and how it affected all their thoughts and actions, principles and policies. (See “Two Views of Justice in the American Founding” for an examination of how the Founders’ moral view of contracts affected their policy prescriptions related to the United States debt and its repayment.)

The Terms of the Debate

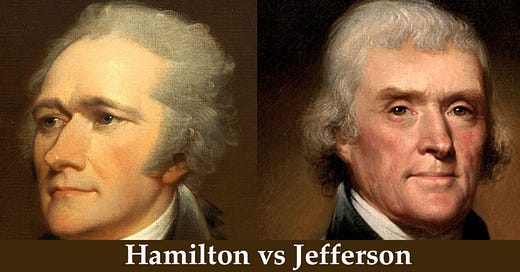

Out of this broader context arose one of the most interesting and complex debates in American political history that pitted two of the nation’s greatest Founding Fathers—Alexander Hamilton (Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury) and Thomas Jefferson (Washington’s Secretary of State)—against one another. More specifically, France’s declaration of war against Great Britain, Spain, and Holland on February 1, 1793 (thus making France’s participation in the war offensive rather than defensive) threatened to drag the new nation into a conflict it had no interest in supporting.

The Franco-American treaties of 1778—the “Treaty of Alliance” and the “Treaty of Amity and Commerce”—imposed certain obligations on both nations. (I shall focus here only on what the United States promised to France.) The so-called “guarantee” clause of Article 11 of the “Treaty of Alliance” imposed certain obligations on France and the United States “from the present time and forever.” The Americans promised “to his most Christian Majesty the present possessions of the Crown of France in America as well as those which it may acquire by the future Treaty of peace.” In practical terms, this meant that the United States promised to come to the aid of France if its West Indian possessions were attacked. Article 12 specified what was guaranteed by Article 11: “the Contracting Parties declare, that in case of rupture between France and England, the reciprocal Guarantee declared in the said article shall have its full force and effect the moment such War shall break out and if such rupture shall not take place, the mutual obligations of the said guarantee shall not commence, until the moment of the cessation of the present War between the United States and England shall have ascertained the Possessions.”

A guarantee is a promise to do something in the future, a promise comes with a moral obligation, and a moral obligation in the eighteenth century was thought to be contextually absolute and binding.

Not surprisingly, the French insisted on strict observance of their 1778 treaties with the United States, particularly those articles in the “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” having to do with privileges promised to the privateers of both nations. The French insisted that by the terms of the treaty, French privateers were permitted to not only bring their prizes into American ports but that they also be permitted to arm and equip their ships while prohibiting the same right to the British.

Interpreting the two treaties in this way would effectively make the United States a French ally in an offensive war, and such a move could be viewed as equivalent to an American declaration of war against Great Britain. To some Americans, then, the 1778 treaties were something of an albatross—indeed, some Americans viewed the treaties in the context of the time as a suicide pact—that seemingly committed them beyond their intentions and expectations in 1778.

Not surprisingly, many Americans interpreted the Franco-American treaties of 1778 differently than the French. At the very least, the “Treaty of Alliance,” as a matter of objective and dispositive fact, was intended for defensive purposes only, which suggested that the Americans bore no moral or diplomatic obligation to support France with military assistance in its offensive war against Great Britain, Spain, and Holland.

George Washington Wants Answers

On April 18, 1793, President Washington sent his four cabinet officers (i.e., Hamilton, Jefferson, Henry Knox, and Edmund Randolph) a list of thirteen questions on how the Executive should conduct America’s foreign policy in the wake of the European war. The first and the fourth questions raised the most philosophic issues.

Question #1 asked: “Shall a proclamation issue for the purpose of preventing interferences of the citizens of the United States in the war between France and Great Britain, &c.? Shall it contain a declaration of neutrality or not? What shall it contain?

Question #4 asked: “Are the United States obliged, by good faith, to consider the treaties heretofore made with France, as applying to the present situation of the parties? May they either renounce them, or hold them suspended till the government of France shall be established.” The fourth question went to the nub of the philosophic issue. To ask if the United States is “obliged, by good faith” to honor its treaties with France is ultimately a moral question. If a treaty is a contract, are the Americans obliged morally to fulfill their promises?

The first question was answered in the affirmative the following day when Washington met with his cabinet. The second question of Washington’s list of fourteen—whether Edmond Genêt, the new ambassador representing France’s revolutionary government should be received, and, if so, in what manner—was also taken up at the meeting. Hamilton opposed receiving Genêt without qualification as it would be tantamount to recognizing the French republic, which meant that the treaties of 1778 were still in force. Jefferson, by contrast, supported both the recognition of Genêt and the continuing legality, obligations, and self-enforcement of the treaties.

The resulting “Proclamation” (note that the word “neutrality” was not used in the “Proclamation” but it was in effect just that) was issued on April 22, announcing “that a state of war exists between Austria, Prussia, Sardinia, Great Britain, and the United Netherlands, of the one part, and France on the other. . . . and the duty and interest of the United States require, that they should with sincerity and good faith adopt and pursue conduct friendly and impartial to war belligerent powers. . . . and to exhort and warn the citizens of the United States carefully to avoid all acts and proceedings whatsoever, which may in any manner tend to contravene such disposition.” Though the word neutrality does not appear in the text of the proclamation, it was nevertheless understood by all parties to support American neutrality.

Washington then instructed Hamilton and Jefferson to prepare written answers to the remaining questions, which he received on May 6. Washington knew in advance of his request that his Secretary of the Treasury was partial to Great Britain and that his Secretary of State was partial to France.

Hamilton and Jefferson both hoped to preserve American neutrality, but what that meant precisely and how it would happen drew these two titans of the American Founding into an extraordinary debate with one another. As we’ve seen, what made the issue difficult for the Americans was that the 1778 treaties with France came with certain obligations. The French had no no doubt acted in their own self-interest in supporting the United States during the American Revolution, not to mention their centuries-old hatred of Great Britain, but it is likewise true that the Americans almost certainly could not have won their war with Great Britain without the aid of France. In other words, the Americans’ debt of obligation to France was real.

The treaties of 1778, which very much helped the United States to fight and win its war against Great Britain, were technically still in effect in 1793 and imposed certain indirect obligations on the Americans. At the very least, the Americans bore some kind of moral if not a legal obligation to support France. On the other hand, France had initiated the war with Great Britain and the United States was hardly prepared financially or militarily to fight another war. In other words, the Americans were stuck between a rock and a hard place. If they honored their treaty obligations with France, they risked war with England; if they suspended or renounced their treaty obligations, they risked war with France.

Questions and Definitions

This vexing situation in 1793 raised an important and difficult question for the Americans: what military and commercial aid, if any, did the United States owe France in its newly declared war with England?

To answer this question, we must step back and ask a series of related or corollary questions. What is a treaty? Are treaties between nations contracts (we’ve already defined what a contract is in “Contracts and the Birth of a Free Society”), and, if so, what kind of contracts are they? If treaties are contracts, must they have identical constituent parts as do other contracts (e.g., property or commercial contracts), or are they a special kind of contract with different conditions and requirements? Who arbitrates treaties when they’re broken? And what were the precise terms of the two treaties signed by France and the United States in 1778 (see above)?

To understand what a treaty is, we must define its essential characteristics and applications. Samuel Johnson’s 1773 Dictionary of the English Language defined a treaty as a “Negotiation; act of treating” and as “A compact of accommodation relating to public affairs.” Noah Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language defined a treaty as “An agreement, league or contract between two or more nations or sovereigns, formally signed by commissioners properly authorized, and solemnly ratified by the several sovereigns or the supreme power of each state. Treaties are of various kinds, such as treaties for regulating commercial intercourse, treaties of alliance, offensive and defensive, treaties for hiring troops, treaties of peace, etc.”

By Webster’s definition, we see that treaties are contracts between sovereign nations. Treaties, like contracts, involve an exchange of promises between two or more parties to do or not do certain actions. The promise to do or not do something is a binding moral obligation, and to default on what one has promised is a dereliction of moral responsibility that causes a harm to the other contracting party.

One major difference between treatises and contracts (at least up until the twentieth century) is that treaties, at least in the context of the eighteenth century, could not be enforced by a neutral third party. There was no international court system in the eighteenth century to adjudicate the violation of treaties. Hence treaties involved honor as the enforcement mechanism, but honor is a weak thread in questions of war and peace.

Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson both viewed treaties as contracts, or at least a certain kind of contract. The main question for Hamilton and Jefferson came down to this: how could the United States remain neutral in the conflict between France and England and still fulfill its treaty obligations to France? More specifically, did the two Gallo-American treaties of 1778 require the United States to defend France’s West Indian possessions?

Preliminaries to the Debate

The Hamilton-Jefferson debate is one of most remarkable in American history. Both men used closely reasoned arguments displaying their mastery of the law of nations, both employed a high level of knowledge and prudence in their understanding of the demands and limits of diplomacy and foreign relations, and both believed that American foreign policy should be grounded in first principles. Rarely has such learning and intellectual fire power been on display. Rarely has such reasoning power and subtlety been used in the creation of American foreign policy. The debate raised fundamental moral, legal, and strategic issues that would no doubt determine the fate of the United States.

Hamilton and Jefferson both supported American neutrality as I have noted already, but they differed markedly in their interpretations of the precise obligations owed by the United States to France and how to discharge those obligations. In their answers to Washington’s fourth question(s)—which was, to repeat: “Are the United States obliged, by good faith, to consider the treaties heretofore made with France, as applying to the present situation of the parties? May they either renounce them, or hold them suspended till the government of France shall be established?”—each drew upon the continental Enlightenment tradition to determine America’s moral obligations. They examined and quoted extensively from Hugo Grotius’s On the Law of War and Peace (1625), Samuel Pufendorf’s Of the Law of Nature Nations (1672), Christian Wolff’s The Law of Nations According to the Scientific Method (1749), and Emer de Vattel’s The Law of Nations (1758).

Before we examine the competing views of Hamilton and Jefferson on the question of treaties as contracts and the moral obligations that follow therefrom, I’d like to mention in passing the different modes of philosophic reasoning or what we might call the political epistemology that our two combatants used in examining this question. Hamilton’s mode of reasoning was strictly based on reason, facts, and logic. The New Yorker followed what he called the pure “dictate[s] or reason,” which he referred to as the “touchstone” of moral and legal “maxims.” Jefferson, by contrast, appealed to “feelings and conscience,” the “head and heart,” and the “moral sense” as the means by which men may discover the “moral law.” The Virginian obviously respected and deferred to reason, which seemed for him to be the vehicle by which one made sense and use of one’s “feelings,” “conscience,” “heart,” and “moral sense.” These different modes of reasoning might suggest that Hamilton was operating with “objective” theory of contracts and Jefferson was using the “intrinsic” theory of contracts. (On this distinction, see “Contracts and the Birth of a Free Society” and “Two Views of Justice in the American Founding.”)

Readers of this remarkable debate are also struck by the overtly moralistic language used by both Hamilton and Jefferson. Strip away the discussion of treaties, alliances, diplomacy, foreign affairs, war, and international law (i.e., the law of nations) and what you are left with in the Hamilton-Jefferson debate is a philosophic contest over the nature of moral obligation. Hamilton speaks of the “right,” “spirit of justice,” “just cause,” “moral duties,” “honor,” “true morality,” “perfect and strict obligation,” and Jefferson speaks of “moral law,” the “the law of self-preservation,” “moral duties,” “natural law,” and “moral feelings.” Fundamentally, this was not so much a debate over foreign policy as much as it was a debate about the nature of moral obligation.

Let us turn now to the arguments of Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson as they debated America’s treaty obligations.

Hamilton’s Argument

Hamilton began his response to President Washington’s query by slightly rephrasing the principal question: “Are the United States bound, by the principles of the laws of nations, to consider the Treaties heretofore made with France, as in present force and operation between them and the actual Governing powers of the French Nation? or may they elect to consider their operation as suspended, reserving also a right to judge finally, whether any such changes have happened in the political affairs of France as may justify a renunciation of those Treaties?”

That Alexander Hamilton viewed treaties as contracts and as contracts with moral obligations is indisputable (i.e., in the same way he viewed the U.S. government as bound by contract to pay current holders of the debt in 1790). Throughout his response to President Washington’s 13 questions, he repeatedly recognized the Franco-American treaties of 1778 as contracts with special moral obligations, but he did think treaties between nations were a special kind of contract with their own unique qualities and characteristics and thus with their own unique moral obligations that were somewhat different from those of regular contracts.

The fundamental question to which Hamilton addressed himself was: What is America’s moral obligations to uphold it treaties with France? In other words, what is the debt owed by the United States to France?

The core of Hamilton’s position on the status of America’s obligation to honor its treaties with France came down to this conclusion: given “the origin, course, and circumstances of the relations originally contracted between” France and the United States and given the current state of France’s internal and external affairs, the treaties between France and the United States should be considered as “temporarily and provisionally suspended,” particularly if such treaties proved to be “disadvantageous or dangerous.”

How did Hamilton work his way to this position? His response to Washington consisted of four primary arguments.

First, he argued the Americans’ treaties with France in 1778 “were made with His Most Christian Majesty, his heirs and successors.” Over the course of the last few years, however, the French government had undergone several revolutions: most importantly, the King had been dethroned, executed, and replaced by a succession of increasingly radicalized governments. At the time of Hamilton’s writing in April 1793, it was not at all clear who was or would be in control of France’s government even in the near future or even month to month. The fact of the matter was that France was in the middle of a civil war the outcome of which was unclear. It was entirely reasonable for the Americans to wait until France’s revolutionary ferment had ended, Hamilton argued, and a new government legally established and recognized by other nations. At best, France had a provisional government, and it was not at all clear if that government represented the will of the nation.

Hamilton recognized the right of the French people to change their government, but he did not think it followed that they had “therefore a right to involve other nations, with whom it may have had connections, absolutely and unconditionally” in courses of action that were “useless, dangerous, or hurtful” to the contracting party. In such cases, the contracting party had a moral right, according to Hamilton, to “renounce” such treaties as incompatible with and detrimental to their original purposes. In sum, Hamilton argued, “Contracts between nations as between individuals, must lose their force where the considerations fail.” Finally, Hamilton posed a not unreasonable hypothetical: imagine if the United States were to support the French republic in its war with Great Britain and then one of the King’s heirs was restored to the French Throne in the middle of the war. The result would be that the United States might potentially be at war simultaneously with Great Britain and France!

Second, another reason for caution in fulfilling the treaties is that the new revolutionary government of France had declared war against Great Britain, which of course meant that France was engaged in an offensive war. The “Treaty of Alliance” was a defensive treaty only, which meant that, strictly speaking, the United States had no moral or legal obligation to support France in its war with Great Britain and its allies. Thus, the “casus fœderis” [the case of the covenant], Hamilton argued, “does not exist.” In other words, the Americans were not bound to their treaty obligations to support France in an offensive war against Great Britain.

Third, following the arguments of the great Enlightenment philosophers on the laws of nature and nations (e.g., Grotius, Vatell, and Puffendorf), Hamilton argued that any alliance determined to be “useless, dangerous, or disagreeable” by circumstances to one party could be legitimately repudiated, and such was the case in the present circumstances with America’s treaty obligations to France.

Fourth, Hamilton distinguished between the “objects” of a contract involving a debt in money versus those of a treaty of alliance, which he thought had “no necessary connection.” Contracts involving debts in money and political alliances between nations are different kinds of contracts governed by different considerations. The terms of a loan, for instance, are clear and well defined in objectively identifiable terms. Consequently, the “payment of a debt,” according to Hamilton, “is a matter of perfect and strict obligation.” Such contracts “must be done at all events . . . and ought to be done with precise punctuality.” This was exactly Hamilton’s position on America’s financial debts to France and all other nations. By contrast, questions of “political connection,” he maintained, are different from those involving property. Political alliances between “nations are capable of being affected by a great variety of considerations, casualities, and contingencies.” The government of one contracting nation may undergo a revolution in its form and purpose such that it becomes anathema to the terms of the original treaty and thus nullify the obligations of the other party. The United States, Hamilton argued, has an absolute obligation to pay its financial debts to France, but it also has the right to withdraw from its political treaty of alliance with France if necessary.

Hamilton’s position can be summed up this way: a treaty is not a suicide pact.

Jefferson’s Argument

Secretary Jefferson began his response to George Washington’s fourth query by likewise rephrasing the President’s original question. Rather than asking what moral obligations the Americans have toward the French in their treaties of 1778, Jefferson asked the inverse of the same question: “whether the United States have a right to renounce their treaties with France, or to hold them suspended till the government of that country shall be established?” In other words, the full question is: does the United States have a moral right to suspend or renounce its treaties with France, or does it have a moral obligation to fulfill its treaty agreements?

Jefferson both agreed and disagreed with various elements of the Secretary of the Treasury’s interpretation of America’s 1778 treaties with France.

Like Hamilton, the Secretary of State 1) believed that treaties are a species of contract with traits like and unlike contracts between individuals; 2) viewed treaties as defined by, and grounded in, the sanctity of moral obligations; 3) supported American neutrality; and 4) thought that only dire necessity could justify suspending or even renouncing treaties. To share this much in common with Hamilton was to be allied with him on all the principal issues. Unlike the Secretary of the Treasury who believed that certain obligations associated with the 1778 treaties could be suspended until the situation in France was clearer, Jefferson believed that, at least for the moment, the United States should quietly act as though it would honor its treaty obligations.

If Hamilton’s strategy were to anticipate future dangers by suspending the treaties or certain articles therein, then Jefferson’s strategy was to delay as much as possible how specific articles of the treaties were to be applied in the present. Here, then, is the core difference between Hamilton and Jefferson: the former wanted to temporarily suspend America’s obligations, whereas the latter wanted to temporarily postpone their obligations. In the end, it was a distinction with little difference.

Theoretically, Jefferson believed that the United States was, broadly speaking, honor-bound to uphold its part of the 1778 treaties, at least temporarily. Practically, the Secretary of State believed that by simply not declaring publicly a position on the treaties (which walked a thin line between supporting and renouncing the treaties), he thought he could bargain for trading concessions from England and France. In other words, Jefferson was engaging in a high-level and subtle form of realpolitik.

The differences, then, between Jefferson and Hamilton on the interpretive and moral questions of treaties were, at least on the surface, differences of degree and not of kind. Both men had an inflated and stern understanding of the moral obligations associated with treaties and contracts, but they were both willing to temporize on those obligations.

Jefferson’s reasoning (based on his “feelings and conscience”) began with two basic premises: first, America’s 1778 treaties with France were with the people of the French nation and not with “Louis Capet”; and second, a change in the form of government of one or both parties to the contract does not change the treaty obligations of either nation. Jefferson argued that treaties are made between nations, not between their governments. This meant that nations may change their government or even their form of government without impairing their treaty obligations.

Jefferson argued that treaty obligations between nations carry the same, or at least similar, moral obligations as between contracting individuals. The Secretary of State then established what he believed the “law of nations,” and its derivative the “moral law of our nature,” required of the Americans. By the moral law of nature, according to Jefferson, the obligations of one man to another in a state of nature are carried forward to the state of society where the aggregate obligations of one society to another mirror those between individuals in and out of society. The Secretary of State argued that treaties between nations carry the same moral obligations via the moral law of nature as do contracts between individuals. But he then admited that some contracts, either between individuals or nations, can be broken when 1) “performance . . . becomes impossible,” and 2) “performance becomes self-destructive to the party.” Non-performance in the former “is not immoral,” according to Jefferson, and the “law of self-preservation overrules the laws of obligations” in the latter. In practical terms this meant that Jefferson was willing to put the survival of the United States above its treaty obligations if, for instance, the West Indies guarantee threatened to drag America into a war.

Even then, Jefferson said the “danger must be imminent, and the degree great.” Unlike Hamilton, the Secretary of State rejected the claim that one party could invalidate a contract or treaty simply on the grounds that it was “useless or disagreeable.” (Hamilton had quoted Vattel’s use of the words “useless” and “disagreeable” as grounds on which one could not fulfill treaty obligations.) Jefferson recognized that the use of words such as “useless” or “disagreeable” introduced a degree of subjectivity into the interpretation of treaties, which would inevitably lead to a “chain of immoral consequences” that contradict “all the written and unwritten evidences of morality.” The use of such concepts, Jefferson argued, was non-objective and beyond evidentiary proof. Besides, Jefferson claimed that the dangers to the United States from its treaties with France were illusory.

The Secretary of State also recognized that in international affairs, unlike regular systems of justice that resolve conflicts between individuals, “nations are to be judges for themselves; since no one nation has a right to sit in judgment over another.” A fundamental rule of justice in a free society is that no man should be a judge in his own case, but Jefferson is clearly saying that nations can and should be judges in their own cause in international affairs. He was simply recognizing a fact of reality that Hamilton no doubt agreed with as well.

Again, the difference here between Jefferson and Hamilton was one of degree and not of kind. Indeed, the degree of separation between Hamilton and Jefferson was minimal. The Secretary of State was splitting the difference between the Secretary of the Treasury’s position of possibly suspending the treaties and the position of publicly stating America’s intention to fulfill its treaty obligations. Jefferson then bore into Hamilton’s position in a way that served to clarify and even improve it.

What Jefferson called the “right of self-liberation” from a treaty (qua contract) was limited, he argued, to three “just limitations.”

First, a nation that absolves itself from a treaty must face a “danger” that is “great, inevitable and imminent.” In Jefferson’s view, the danger to the United States at the present moment was neither “great” nor “inevitable” or “imminent.” The Secretary of State believed that if the United States were to simply do nothing for the time being, it would avoid potential future conflict and avoid war with both Great Britain and France.

Second, the right of self-release was limited solely to those clauses in a treaty that would bring “great & inevitable danger on us” but not from the treaty as a whole. In Jefferson’s view, if some part of a treaty put the United States in danger that was great, inevitable, and imminent, then the U.S. could extricate itself from its obligations to those clauses or promises, but not from the rest of the treaty.

Finally, a nation’s right to self-liberation from a treaty or the relevant parts comes with a moral obligation “to make compensation where the nature of the case admits & does not dispense with it.” Jefferson does not explain what constitutes “compensation” or how or by whom it would be determined, but he does think that a non-fulfilling nation is morally bound to pay some kind of compensation for not fulfilling its treaty obligation.

In the end, Jefferson’s analysis and critique of Hamilton’s position should not be viewed as a rejection as much as an improvement of it. And of course, the reverse can be said as well.

Conclusion

After he had received reports from his two secretaries, President Washington effectively split the difference between Hamilton and Jefferson. On the one hand, he sided with Hamilton on the need to issue a proclamation of neutrality. On the other hand, he sided tactically with Jefferson’s interpretation of the treaties: Citizen Genêt would be received without qualifications, and the Franco-American alliance would be maintained for the time being. As result, the United States became the first nation in the world to recognize the French republic.

What is most important about the Hamilton-Jefferson debate is not what it tells us about their views on international affairs, diplomacy, foreign policy, or even treaties, but what it tells us about the Founders’ views on the moral status of contracts in a free society. Contracts are the moral ligament that holds a free society together. At an even deeper level, the debate provides one entry point into the Founders’ views on the moral obligations of individuals and nations in a free, just, and decent world. Once we truly and fully understand the Founders’ moral views, we can then better grasp and appreciate the kind of society that issued from the American Founding.

**A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.

Have a great week!

What leaps out of every paragraph of this article is the impressive level of thought shown by each of the two disputants. Can one think of any two similarly intellectual, deeply knowledgeable political figures (say any of our current cabinet secretaries) today, who could in a matter of a few weeks reply to their President’s request for advice on such a weighty matter, as these two men did? Stunning!

What this shows is just how difficult it is to apply Objectivist moral and political principles to a world that doesn't understand them philosophically. And this obviously continues today. Not that Hamilton and Jefferson were Objectivists, but they were (and probably still are) the best representatives of a political philosophy of individual rights that have ever run a government. And yet, they and George Washington were obviously having great difficulty honoring a legitimate debt to a government that was the antithesis of a protector of individual rights. Their country wouldn't exist without French help, but they couldn't in good conscience support such a regime's quest for power. They also couldn't in good conscience deny the very real indebtedness to the people who had literally rescued them in their hour of need. Until 'protecting individual rights' becomes the dominant reason and purpose for governments in the real world such difficulties will continue to arise.